Diversity is the Wellspring of Innovation

Respecting Individuality and Creating Appropriate Environments for the Realization of a Society Where Everyone Can Thrive Authentically

Talk Show ‘Towards a Neurodiverse Society’

B Lab, dedicated to creating an interesting future together, has launched the “Neurodiversity Project” with the aim of building a society where each individual can demonstrate their unique strengths in their respective places. As the first initiative, an exhibition titled “Everyone’s Brain World – Neurodiversity Exhibition 2023” was held during the event “CHANGE TOMORROW ” which took place on September 17 and 18, 2023, at Tokyo Port City Takeshiba. This summary introduces the talk show held on the 18th, focusing on the theme “Towards a Neurodiverse Society.

“Toward a Neurodiverse Society”

■Date: Monday, September 18, 2023, 1:00 p.m. – 2:00 p.m.

■Speakers :

Joichi Ito (President, Chiba Institute of Technology)

Junichi Ushiba (Professor, Faculty of Science and Technology, Keio University)

Kouta Minamisawa (Professor, KMD, Keio University)

Ory Yoshifuji (CVO, President and Representative Director, Ory Research Institute, Inc.)

■Moderator: Nanako Ishido (Director, B Lab)

Neurodiversity Project is an initiative to promote a society where everyone can live more comfortably and unleash their potential

Ishido: Have you ever heard of the term ‘neurodiversity’? It is about recognizing the diversity in the human brain and nervous system, each with its own unique characteristics. The idea behind neurodiversity is to embrace these differences as strengths. In our pursuit of creating a society where each person can showcase their abilities in their own way, we’ve launched the Neurodiversity Project. The first initiative is the ‘Everyone’s Brain World: Neurodiversity Exhibition 2023.’ We’ve teamed up with various leading universities, research institutes, and companies in Japan to present 33 exhibits, showcasing the richness of neurodiversity.

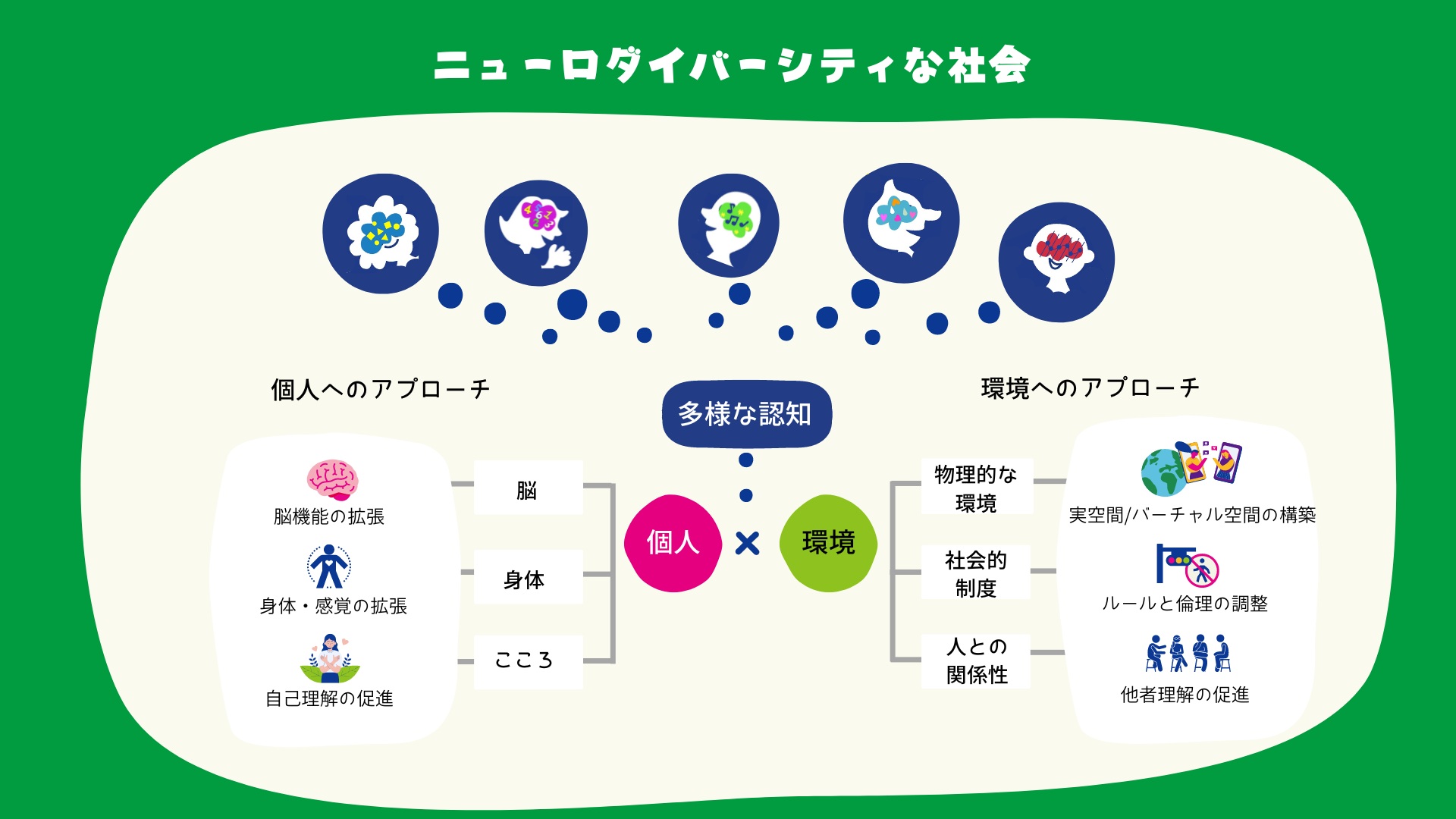

Now, every person has their own individuality and traits, but as a result, some may find life challenging. At times, individual traits, such as neurodivergence, are even described as if they are the problem. However, the difficulty these individuals experience isn’t solely due to their personal traits. It arises from the interaction between individual characteristics and the environment.

In other words, depending on the environment, these individualities and characteristics can become significant strengths. For instance, many historically influential inventors and entrepreneurs who have had a profound impact on society have openly discussed having neurodivergence. However, by placing themselves in environments that allow them to leverage their unique traits, these individuals have turned their neurodivergence into “strengths.” People with identical traits may, depending on the environment, become charismatic leaders or face challenges in employment. Therefore, we believe in respecting individuality, eliminating challenges by creating suitable environments, and striving to realize a society where everyone can thrive and contribute in their own way.

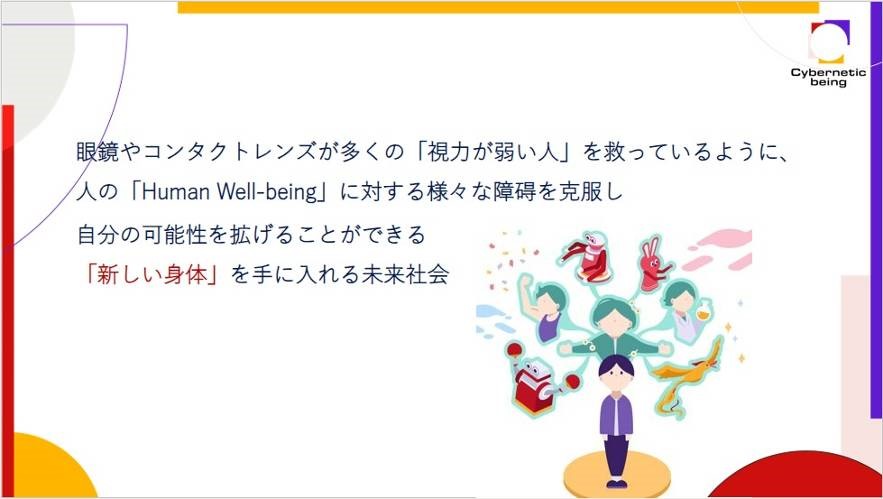

We are pursuing two approaches to address these challenges. One is an initiative to enhance individual abilities through technology. For example, consider eyeglasses. In a time without glasses, life might have been challenging for those with poor eyesight. Nowadays, we don’t consider poor vision a disability. Furthermore, some people wear glasses as a fashion statement. Through technology that enhances the body and brain functions, possibilities for individuals expand significantly.

The other approach involves adjusting the environment. Our daily lives are influenced by various factors such as physical surroundings, social systems, rules, customs, and relationships. For instance, individuals with color vision deficiencies may find it challenging to distinguish between red and green signals at traffic lights. However, if it were possible to see with different colors, changing the traffic signal colors could be considered to reduce the challenges in daily life. Similarly,there are children who, due to sensory sensitivities, find school uniforms heavy or experience discomfort on their skin, leading them to be unable to attend school. If there were no rules mandating the use of uniforms in the first place, these children might be able to attend school without any issues. In this way, we are working towards creating a more accommodating society by adjusting the environment.

At the ‘Everyone’s Brain World: Neurodiversity Exhibition 2023,’ we have organized exhibits under five different sections, exploring themes such as ‘Expanding Individual Abilities’ and ‘Adjusting the Environment.’

Please take a moment to explore the exhibits from the perspective of ‘Realizing a Neurodiverse Society through Individual Empowerment.’ Rather than just saying, ‘Oh, I see,’ I encourage you to think about ‘How can we create a society where everyone can live comfortably?’ and ‘What actions can I take personally?’ This talk session will also delve into discussions from that perspective.

Now, let’s hear from our speakers. Under the theme of ‘Presentations on Neurodiversity’, first, I would like to start with Joichi Ito, President of the Chiba Institute of Technology.

Many Geniuses Are on the Autism Spectrum

Creating an Environment for Unleashing Abilities is Crucial

Ito: MIT has 98 Nobel laureates, with many being on the autism spectrum. While not all individuals with autism are geniuses, the prevalence of brilliance highlights the spectrum’s diversity.

In the United States, there is a culture around individuals with autism, and understanding and support for them have advanced significantly, establishing a culture that respects their unique qualities. Japan, on the other hand, has historically strived to create a standardized workforce, with everyone aiming to become a corporate employee in a major company. When individuals who don’t fit the standard mold emerge, their unique strengths are often overlooked or dismissed, reflecting the current reality. Therefore, I believe we need to change a society where prioritizing standardization is seen as the top priority and where ‘conformity is a must.’

As a personal anecdote, while conducting research on the autism spectrum at MIT Media Lab, a colleague jokingly remarked, ‘Raising a child with autism is very challenging, and we urgently need experts in autism. It would be nice if Ito-san’s child turned out to be autistic.’ Then, my daughter was born with autism.

Returning to Japan with my daughter, I felt that the environment for autistic children in Japan was lagging. Feeling a need to do something about it, I decided to launch a program in 2024 that integrates children with autism and those without, initiating activities in Japan.

Ishido: Thank you very much. Next, we have Professor Kouta Minamisawa from Keio University Graduate School of Media Design.

Research on Acquiring a ‘New Body’ to Expand One’s Potential

Minamizawa: We are conducting research on ‘Embodied Media,’ exploring what new possibilities arise when the body is connected to technology. We are developing technologies such as robots, virtual reality, and tactile reproduction to enhance sensory experiences.

First, there’s “Dementia Eyes.” When wearing a Head-Mounted Display (HMD), one can immerse oneself in the world as perceived by individuals with dementia, experiencing distorted space, unclear distances, and difficulties in sitting on a chair. Actual caregivers and doctors cooperated in the development of this project. Those who experience wearing the HMD find that their approach and communication with patients change afterward.

One of our research focuses on the “Expansion of the Individual.” For instance, in a project called “Aique,” we explore the idea of designing one’s body, contemplating what new possibilities might emerge if humans had tails.

In another project called “Musiarm,” we extend the technology of attaching tails to the arms and apply it to limbs. With the collaboration of an individual without the lower part of the right arm, we developed a device where the arm itself transforms into a musical instrument, aiming to fulfill the desire of playing music. These projects aim to realize a society where it’s acceptable for everyone to have different bodies, allowing individuals to become the person they aspire to be.

This research culminates in the ultimate form showcased in this exhibition, the performance by Masatomi Muto, a person living with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). ALS is a progressive disease resulting in the gradual loss of bodily functions. However, using eye movement for communication and employing BMI to control a robotic arm, Mr. Muto was able to engage with the audience and create an uplifting atmosphere. Building upon these research achievements, we are conducting studies under the theme of ” Creation of Society.” Collaborating with Mr. Yoshito Ory, who will speak next, we are working to create a world where people unable to leave their homes for various reasons can still engage in various activities and participate in society. Through this initiative, we aim to generate new ways of working and learning.

Similar to overcoming disabilities with glasses or contact lenses, we are advancing research that combines new bodies with new technology to create a new society.

Ishido: We have received an introduction to the possibilities expanding in the brain and body through the utilization of technology. Finally, we have Mr. Yoshifuto Ory, CEO and Chief Visionary Officer of Ory Research Institute, Ltd.

Using Doppelgänger Robots to Expand “Communication Skills” and Alleviate Human Loneliness

Ory: When I was a child, I couldn’t attend school much. I was physically weak, hospitalized, and mentally unstable. Although I’m referred to as Ory, my real name is Kentaro Yoshifuji. Healthy, chubby, and cheerful – that’s what Kentaro should have been. However, it was completely different. I despised that name and was the kind of child who would continue to ignore anyone calling me Kentaro. The dissonance between my name and appearance meant that I could no longer recognize myself. This state persisted for a long time. The emergence of self-awareness and metacognition was much slower for me than for others.

Unable to establish my identity and in a floating state, I couldn’t find a place for myself at school. When I became a truant due to feeling different from others and the difficulty of living, I truly felt loneliness. During those times of not attending school, I felt incredibly lonely with nothing to do. Staring at the ceiling, I even began to forget Japanese. I even forgot how to laugh.

Despite these experiences, in high school, I became involved in the invention of a new mechanism for an electric wheelchair. I won the High School Science and Technology Challenge, received the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology Award, and participated in the world competition. However, at that time, I realized that I didn’t want to create a wheelchair; I wanted to create something that would eliminate the loneliness felt by people who couldn’t go outside without a wheelchair, causing them to confine themselves at home. So, I developed the telepresence communication robot ‘OriHime’ that allows people to communicate remotely. Abilities and strength were mentioned earlier. I underwent cyborgization through surgery for implanting ICL contact lenses in my eyes, eliminating visual impairments. The wheelchair supports leg strength. There is an interpretation system for English proficiency. However, there was nothing for communication skills. Therefore, I conducted research on supporting communication skills and established a research institute named ‘Café’ for that purpose. We created prototypes in an underground laboratory and experimented with them in front of customers, repeatedly apologizing when things went awry – essentially creating the ‘world’s most failing cafe.’ In this telepresence robot cafe called DAWN, the robots are operated remotely by individuals who are socially withdrawn, unable to attend school due to illness, unable to return to work for an extended period, or experience panic when in public. These individuals can control the robots from a distance. With the use of these robots, they can speak in public and even engage in customer service.

Earlier, I talked about the concept of self-identity. The name “Ory” comes from my love for origami, which I practiced throughout my hospitalization. The black visual aesthetic also dates back to when I was 18, and I have continued to wear black for half of my life. I have established my identity through this appearance and the name Ory. I believe that online games share a similarity with this. For those who struggle to find their place in the real world, online games provide a space where they can immerse themselves and make friends.

If diving into a VR space requires a head-mounted display, then this robot serves as a device for residents of the VR world to dive into the real world. This allows hospitalized children to attend school and speak in public.

Using various devices, individuals who, for example, can only move their eyes due to conditions like ALS can operate devices solely with their eyes and create drawings.

I genuinely believe that it is precisely because something is challenging that it is worth pursuing, and there is value in the things that seem impossible. I am dedicated to creating new systems that enhance the abilities of individuals facing such challenges. The ultimate goal I am aiming for is the ability to care for oneself when unable to move the body. Being able to handle personal tasks independently is crucial for establishing one’s identity. Through the development of the robot OriHime, I am engaged in research on devices that provide a sense of accomplishment, allowing individuals to feel that they have done things themselves and can reciprocate for the help they receive from others.

Diversity is the wellspring of innovation for society

Ishido: Thank you very much. We mentioned the terms ‘school refusal’ and ‘social withdrawal,’ but listening to the stories, I started to think that we might need to update the definitions of these words. Is attending school the only definition of going to school, or can engaging in activities that fulfill one’s life, even if done online, also be considered avoiding social withdrawal? That’s something I pondered based on the discussions.

Ory: There is someone here in this venue who says, ‘I always find it exhausting to be in a crowd, but today I tried blending into the crowd with OriHime. It’s the first time in my life.

Ishido: Certainly, individuals with auditory sensitivities, for example, can use OriHime to block out sounds when they find it challenging. This makes it easier for them to adjust the environment to their comfort when needed.

After hearing the stories from the four speakers, I feel that we’ve glimpsed new hopes for the future. However, let’s return to the theme of Neurodiversity. I’d like to ask Joi about it. The term ‘Neurodiversity’ is not yet widespread in Japan. It seems like we might be lagging behind compared globally. How do we stand in comparison to overseas?”

Ito: In the United States, due to a long history of racial discrimination, Neurodiversity has become a new human rights issue. In the 1960s-70s, doctors used to treat autism, but later, parents initiated a movement from ‘let’s make them normal’ to ‘it’s okay to be yourself.’ Recently, there’s a strong movement among individuals to ‘prioritize their own happiness.’ Therapeutic methods have become quite diverse. Japan seems to be a bit behind in these aspects. However, in the U.S., there are many technologies focused on supporting from the perspective of adapting to the normal, and there isn’t as much admiration for Neurodiversity. I haven’t seen initiatives like Ory-san’s in the U.S. Japan has always had a culture of various forms of admiration within communities, such as the ‘otaku society.’ Properly incorporating such culture, I feel that Japan’s approach to Neurodiversity won’t necessarily be inferior to that of overseas. I thought that linking the U.S. movement with Japan’s innovation could create something meaningful.”

Ishido: In our project, in addition to solving challenges with technology, we also emphasize the importance of developing technology and building environments together with parties concerned. I would like to hear your opinions on this.

Ory: I once brought OriHime to a gathering of individuals aiming to support people with disabilities, and I was told, ‘It’s the first time a person with a disability has come.’ There were instances where the atmosphere froze when I expressed opinions as a person with a disability. Until then, the predominant perspective was often from the caregivers’ point of view, focusing on how to introduce technology to make caregiving easier.

There was nothing like OriHime, serving as the alter ego of a stakeholder, moving together. After realizing this, I started thinking about person involved, caregivers, and technology. Recently, even those who support these initiatives have been enjoying the evolution of technology, alongside others. I feel that it’s essential for this to permeate the community.”

Minamizawa: Since around 2015, there has been a significant shift in technology, with 3D printers, VR, and more recently AI becoming accessible to everyone, whereas they were once exclusive to experts. This change has made it easier for stakeholders to express their preferences and ideas, saying ‘I want to do it this way’ or ‘Let’s create something using this technology. Now, we are taking another step forward, considering how to firmly install that into society. There are projects like carrying OriHime into a store like a guide dog and movements to change societal rules to realize the world of anime and manga. I find these developments interesting.”

Ishido: Last year’s “Change Tomorrow (Chomoro)” featured a Halloween parade with robots walking through the city. However, there were various regulations even for robots walking on the roads. Chomoro serves as an opportunity to clearly identify bottlenecks in implementing technology into society.

The technologies showcased in this exhibition have been developed as means to assist with life challenges and difficulties. However, I believe it is crucial to take a step further and consider the perspective of ‘Shouldn’t we change the conventional notion of “normal”?’ From this standpoint, questioning whether the previous notion of normality should be altered leads to a significant discussion. I want to connect this to the idea that it might be better for the current ‘normal’ to change, and that using technology can result in a more updated society. The vision we aim to achieve through the Neurodiversity Project is precisely what should be commonplace in the next era.

I also think that societal acceptance is likely the biggest bottleneck. Regarding what Joi initially mentioned, the standardization and conformity pressure in Japan, how do you perceive these aspects compared to other countries?

Ito: Last year, the United Nations criticized Japan quite harshly. Despite claiming to support people with disabilities, Japan has a system where only standardized individuals can attend regular schools. What this implies is that ordinary people believe ‘there are only ordinary people.’ In English, the term for the standard brain is called “neurotypical,” and there is a concept known as “neurotypical syndrome.” This refers to individuals who consider themselves normal, have confidence in that perception, and are more concerned about how others perceive them than questioning factual information. There are many of these individuals in Japan.

The concept of “normal” in Japanese society is not truly normal. It’s crucial to note that what is considered “normal” has been defined without the inclusion of individuals with disabilities. I am working on creating a school where both neurotypical and autistic children can attend together. During a presentation on this idea, a certain authoritative figure commented, “Parents of normal children don’t want their kids mixed with disabled children.” While I wanted to respond, “No, without mixing, they might grow up to be adults like you,” I refrained from doing so. Such attitudes from influential individuals pose a risk to Japanese society.

There is a belief held by some that individuals with disabilities cannot contribute to society, which I consider a form of poverty in mindset. If spaces like today’s event become commonplace, I believe this mindset could improve.

Ishido: As you mentioned, I believe the situation in Japan might have been that the concept of ‘normalcy’ followed the exclusion of individuals not considered as ‘able-bodied.’ That is perhaps why there have been United Nations recommendations on inclusive education in Japan. It might even be embarrassing to acknowledge the necessity of creating spaces in this exhibition for experiencing the differences in each other’s senses. However, as a transitional phase, I think it is important to share information and collectively contemplate these matters.

“Designing a new self” was mentioned. I think the next era involves using technology to live authentically, designing oneself, and shaping the surrounding environment. I wonder, by around 2050, how do you envision designing your authentic self and under what circumstances?

Minamizawa: In 2050, I’ll be around 70 years old. Currently, it seems that there is a trend where we “showcase” various aspects of ourselves through platforms like social media. In the future, I hope we can create a society and utilize technology in a way that expands our understanding of ourselves—acknowledging that the true self is capable of certain things or has experienced certain aspects, shaping who we are today. By accumulating diverse experiences individually, the worlds of each person can expand, and our various experiences are, in fact, supported by technology in various forms. I envision such a society.

Ory: In 2050, I’ll be around 60 years old. It might be early to consider it as old age. I have had a frail body, and when I was 17, I seriously thought that I would die at 30. So, I made a life plan for the next 30 years, wondering what I could achieve in the remaining 17 years. However, being aware of the end was very effective. It allowed me to cherish each day and choose a life without regrets. Having choices at the time when I want to do something important is crucial. The ‘me’ at night is different from the ‘me’ in the morning, and the ‘me’ when hungry is different from the ‘me’ when full. I want to use technology to create options.

Due to my work, I have met many individuals who are unable to leave their bed. I have been contemplating what it would be like when I become bedridden in my old age. While money and hobbies are important, I believe relationships are the most crucial. I have seen situations where someone, despite having wealth, status, and children, is left neglected, while another person with ALS, unable to leave their bed but surrounded by cheerful helpers, seems happy. The critical factor seems to be relationships. To create a situation where people gather even if they are unable to leave their bed, what may be needed is the ‘social skills of a snack bar mama.’ Recently, I’ve even put up a sign saying ‘Snack OriHime’ in the telepresence robot cafe. In a sense, it’s like ‘Snack Tech,’ and that’s my recent research theme.

Ishido: In fact, I’ve always admired the idea of becoming a mama-san at a snack bar.

Ory: You can even be a mama-san at a snack bar remotely.

Ishido: I’d like to do that. Snack Mama has been on my list of things I want to do for quite some time now.

Ory: You can consider a career beyond being confined to bed.

Ishido: I’ll seriously consider it. The use of the term “disability” was a significant point of discussion in this exhibition as well. The debate revolved around what should be considered a disability. For instance, in the environmental exhibit, there is a square-wheeled bicycle. On a flat surface, a bicycle with round wheels moves more easily, while a square-wheeled one has difficulty. However, on a bumpy surface, the square-wheeled bicycle can actually move more smoothly, whereas the one with round wheels may struggle. It varies depending on the environment. Determining what qualifies as a disability becomes challenging, as it depends on various factors, including the environment. Joi, what are your thoughts on this matter?

Ito: In 2050, I’ll be 84 years old. A few years ago, I invited a doctor to Japan and held a two-day conference on his research. He was in his 70s and said, “There is nothing I know that you all don’t know. I can die in peace now.” My ideal for the future is that everyone has access to the knowledge I have today through a network. I hope there will be many successors and students who are better than me at what I’ve always wanted to do, and even after I’m gone, my dreams will continue in society. With the advancement of technology, I believe that by around 2050, there will be systems that can effectively realize what I’m thinking better than I can. Instead of wishing to live forever, I’ll retire.

Ishido: I hope you continue to stay active and live on indefinitely. It would be a loss if you didn’t.

Unfortunately, it’s about time to wrap up, but before we conclude, I’d like to hear your message on ‘Towards Achieving a Neurodiverse Society.

Ory: When thinking about diversity, instead of just trying to understand it, please become friends with individuals who are directly involved. The era is approaching when people with disabilities will become more familiar to us, including those with severe physical limitations.

Minamizawa: As times and technology continue to evolve rapidly, it’s essential to assume that what was once impossible will become achievable. I hope we can collaboratively explore how to create new lives for ourselves and contemplate how we want to shape our own destinies.

Ito: Rather than focusing on strengthening children’s weaknesses and neglecting their strengths, I believe it’s crucial to expand their strengths. Many children express themselves as artists when they are young, but as adults, they often stop doing so, which can be attributed to a loss of confidence. In English, it’s called ‘Creative Confidence’—the confidence to change the surroundings. It’s essential to ensure that children do not lose this confidence and continue to nurture it.

Ishido: When creating this exhibition, I wanted to build it on the foundation that diversity is the source of innovation. Acceptance of diversity is now often referred to as ‘Diversity and Inclusion,’ but even achieving gender diversity has proven challenging in Japan. To truly realize a society that embraces diversity, I believe it requires active social participation from each individual. I hope we can work together to create a new future. Thank you all for joining us today.