Understanding and respecting the diversity of the brain Realize a society where people from all walks of life can live comfortably and comfortably

12/24/25

The Neurodiversity Project, sponsored by B Lab, aims to realize a society in which the diversity of the brain and nervous system is respected and everyone is able to demonstrate their abilities in their own way. In this Neurodiversity Project interview series, we introduce the efforts of Dr. Ryuma Shineha (▲Picture 1▲), Associate Professor, Graduate School of Media Design (KMD), Keio University. The development of neurotechnology has brought about many possibilities. At the same time, it is essential to address Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (ELSI) for better utilization of neurotechnology. In “Brain World for Everyone,” Dr. Shineha introduced the ELSI discussion on neurotechnology and the guidelines for utilizing brain information developed by Center for Information and Neural Networks (CiNet). Nanako Ishido (▲Picture 2▲), Director of B Lab, asked Mr. Shineha about his research activities.

> Interview videos are also available!

To ensure proper use of brain information

8 ethical standards as guidelines

Ishido: “Dr. Shineha exhibited at “Brain World for Everyone” for the first time this year. Please tell us about Dr. Shineha’s research theme and the contents of this year’s exhibit.

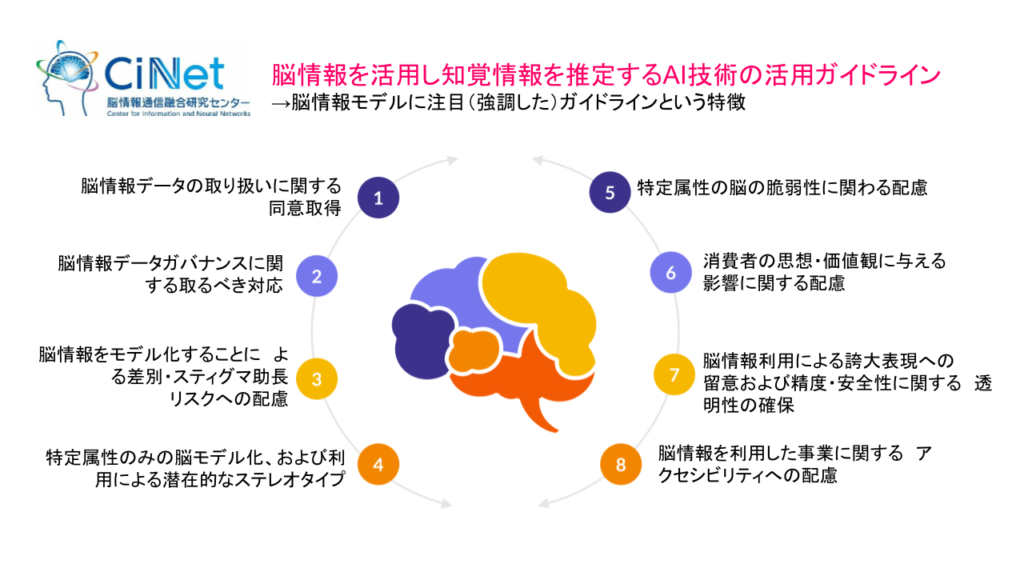

Dr. Shineha: “In addition to my research at Keio University, I also exhibited my activities as a cooperative researcher of CiNet (Center for Information and Neural Networks) at this year’s “Brain World for Everyone. CiNet has established ethical guidelines for the use of “brain information models,” an AI technology that uses brain information to estimate perceptual information. The contents of the guidelines were presented at “Brain World for Everyone”.

In the utilization of brain information, advances in technology, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), have made it possible to acquire a variety of data, which can then be used to develop new technologies and AI.

However, it is important to think about how to use these AI technologies well and how to utilize them in a better way, and to think about the rules of utilization by ourselves in advance, or to send out a message that says, ‘This is how we want them to be used. With this in mind, CiNet has created guidelines and issued a message with eight ethical standards. (▲Picture 3▲)

Since we are dealing with brain information, we are taking into account the latest information on data governance. When it comes to the brain, it is easy to stereotype people with this kind of brain as having this kind of tendency, and there is a concern that this may lead to discrimination and bullying. We oppose such stereotyping and discrimination, and send out the message that we want to eliminate such stereotyping and discrimination.

In addition, the area of neuromarketing is currently undergoing rapid development. Neuromarketing is a marketing technique that measures and analyzes brain waves, eye gaze, and other biological signals to reveal consumers’ unconscious reactions, emotions, and preferences. Depending on how the brain information is used, it can have a significant impact on consumers’ thoughts and values. It sends the message that consideration needs to be given.

Furthermore, it is expected that various services using brain information will appear in the future. We need to think about accessibility to such services and make sure that many people can use them in a fair and equitable manner without any disparities. There is also a concern that technology will become “something only for the rich. We have created ethical guidelines with the message of realizing a world in which a variety of people can freely use the technology.

In Brain World for Everyone, we presented these messages and introduced the trends in neuroethics (neuroethics) that are behind them.

Neurotechnology is in a transitional period of research and development

That’s why the code of ethics and rules need to change.

Ishido: “I feel that it is very interesting to know when and under what context such guidelines are created. The fact that guidelines are needed is an indication that the technology has reached a certain level of maturity and has advanced to the implementation stage. In that sense, I would like to ask, to what level has neurotechnology reached today? And what kind of things have become possible that led to the decision that guidelines are necessary? Could you tell us about the background and reasons for this?

Dr. Shineha: “Technology is evolving rapidly. It is now possible to reproduce, to some extent, what kind of task a person was performing or what kind of images he or she was looking at, based on brain waveforms. AI models utilizing such data are actually in operation. Some of them have already been used in the area of neuromarketing. As social implementation of these latest technologies begins, there is a growing momentum that rule-making for better use of such technologies is indispensable. I myself agree. Under such circumstances, there is a worldwide movement to make rules for better use and to seek how to use them to realize a better society, and Japan is of course no exception.

Looking at the situation in other countries around the world, it is a matter of trial and error as to “how best to utilize the system. As each country is monitoring each other’s situation, examples are needed in Japan as well. However, there are still very few attempts to make rules and guidelines involving neuroscience experts, researchers in the field of social science such as myself, and industry. I am working on this project in the hope that it will be the first such case study, and that it will be useful for many people involved in neurotechnology research and development.

Ishido: “Rules based on technology, such as ethical guidelines for AI and protection of personal information, have been established in the past. However, because we are dealing with brain information, I feel that there are unique difficulties and points to be considered that are different from those in other fields. What do you think are the unique risks and issues that arise because of brain information, and what points in particular should we pay attention to?

Dr. Shineha: “I think it is common with the discussion of AI that the perspective of personal information protection becomes important. However, in the case of brain information, I think it is somewhat image-based. It is easy to get the impression that it is more sensitive information. It is easy to have the image that information closer to the inner self is handled, including the sci-fi aspect that “the inside of the brain may be seen” and “what we are thinking may be revealed,” and in fact such research and similar research is being conducted. This is the difference from AI. I feel that this is the difference from AI.

Neurotechnology is characterized by the fact that it is in a transitional stage of research and development, and various technologies are being developed day by day. Therefore, the usage and rules of how to use these technologies need to change, and in the midst of this search, I think it is important now for everyone involved to find a line that everyone can agree on at a minimum.

Neurotech using brain information

Ensuring transparency is a prerequisite for social implementation.

Ishido: “I believe there is a tradeoff between convenience and risk in any technology. However, it is also true that social implementation moves forward precisely because convenience is realized to a certain degree. In the “Brain World for Everyone” exhibition to date, there have been efforts to lower the hurdles to social participation by understanding the psychological states of people who have difficulty communicating and supporting their communication.

I believe that Dr. Shineha fully understands the potential of these technologies, which is why he emphasizes the need for guidelines in order to utilize them more appropriately and move forward. So I would like to ask you, what kind of new possibilities do you think such neurotechnologies will bring about in terms of support and social participation for people with neurological diversity? From your own perspective, how do you see its potential?

Dr. Shineha: “As we are able to obtain various types of brain information and data, we are also making progress in understanding the diversity of the brain, for example, how it is very weak and sensitive to certain types of stimuli. We hope that this kind of technology will be used to develop services that will help people with these characteristics live better and more comfortably.

However, the opposite is also true: services that take advantage of vulnerabilities can be created if one is so inclined. This is why we are sending out the message that consideration must be given to specific brain vulnerabilities and that we should refrain from developing services and technologies that take advantage of such vulnerabilities to make profits. From the perspective of neurodiversity, we would like to respect that and create a world where people of all walks of life can live more comfortably and pleasantly.

Ishido: “I completely agree. We must avoid a situation in which technology developed to enrich the lives of many people ends up making life difficult for others. On the other hand, the question of where to draw the line is a very difficult one. Today, emotions, personality, cognitive characteristics, and abilities are being visualized with a certain degree of accuracy based on brain information, and while this has the potential to deepen self-understanding and promote understanding of others, there is also the risk of having the exact opposite effect, depending on how it is used. Therefore, how much should be allowed, how much should be restricted, and what should be kept in mind when actually implementing it in society? We feel strongly that it is difficult to draw such a line. Could you tell us what kind of discussions are currently being held on this point, and what kind of ideas are shared on how to draw the line and what points to keep in mind when implementing in society?

Dr. Shineha: “You are right, and it was a big discussion about the difficulty of drawing the line. In fact, it can be said to be a case-by-case basis. Even if the content is the same, it could be influenced in a positive or negative way depending on the characteristics of the person. Being on a case-by-case basis was a big part of the discussion.

However, it is necessary to ensure transparency of the content of the R&D and services in order to verify the impact of either perhaps. Furthermore, before that, we need to make efforts to increase transparency by opening up as much as possible the transparency of the technical content, i.e., findings such as ‘how data is being utilized’. From the perspective of neurodiversity, this may also be very important in minimizing negative impacts, which is what we spent the most time discussing.

One major conclusion is to focus on ensuring transparency first, which is very important when considering actual operations.

Who is allowed to use brain information and how to use it

Discussion and rules need to be created

Ishido: “You mentioned that such discussions have started worldwide. I would like to ask you, do you think that the direction of discussion in each country is generally the same, or are there significant differences from country to country? Also, I would like to know about the current position of the ELSI (Ethical, Legal and Social Issues) debate in Japan, whether Japan is making progress or lagging behind when compared to international trends. I would be very interested to hear about Japan’s current position in the discussion of ethical, legal and social issues.

Dr. Shineha: “Globally, various organizations are now issuing reports and draft guidelines. Most recently, UNESCO is about to issue a new document. Others, including the OECD and UNICEF, have issued reports on neurotechnology and its impact on children, particularly in trying to prevent negative effects. I am sure that this is an area that is attracting a lot of attention.

In Japan, the national government has not yet issued any major guidelines. Rather, research institutes actually conducting R&D, such as CiNet, with which I am involved, and individual research projects are creating their own guidelines and issuing their own messages. Specifically, the CiNet guidelines that we created and the guidebook created by ALAYA Corporation for “AI x Neurotech,” which is participating in Goal 1 of the Mooshot project, are two relatively prominent examples. In fact, these are the two examples of Japan that are mentioned in the OECD guidelines.

Ishido: “From this perspective, which country is leading and driving the discussion as a nation at this time?

Dr. Shineha: “For example, from 2014 to 2015, the United States issued a series of ethical guidelines related to neuroscience, or a series of heavyweight reports about it. It was also tied to a large program called the Brain Initiative, which was actively sending out messages, so the U.S. was still one of the countries that led the discussion from the mid-2010s.

Other human green projects were also promoted by the European Commission of the EU, and various discussions were held. The EU was also a leader in the brain science debate in the 2010s. In particular, the United Kingdom issued a separate report, so I think it is fair to say that some of these advanced countries were leading the discussion. In the context of this trend, I feel that Japan is a little behind the curve.

Ishido: “I would like to ask two additional questions: First, if Japan is lagging behind in this field, what is behind that? In the field of brain science and neurotechnology, too, are there big differences in the way people perceive and the direction they take in different countries? Could you tell us about these two points?

Dr. Shineha: “From the latter point of view, I believe that different countries probably perceive it differently. Some countries are more upfront about social implementation, and some countries are trying to guarantee rights for this purpose. In Chile in South America, discussions are quite forward-looking, and I think they are accumulating knowledge. After all, the way of perceiving and tackling the issue differs from country to country. In fact, brain science researchers are developing lobbying and advocacy activities to influence policies and institutions and encourage discussion, and I have heard that this is having an impact as well.

In the case of Japan, for example, when the US or EU conducts major brain science research projects, we have been discussing ELSI and rule-making in parallel with them, but other than that, we have not been very active in this area. As a result, we tend to ‘fall out’ of the international discussion network. In the Asian region, China and South Korea have been more proactive in making investments and inviting international conferences, so Japan is at a bit of a disadvantage.

Ishido: “The same is true of AI, but even when we understand the risks, we can be taken in unknowingly. For example, there have been reports of cases where AI was used as a substitute for counselors for the purpose of psychological care, but ultimately led to undesirable results.

In this light, what is your view on the meaning of technology’s unconscious entry into people’s hearts and minds, Dr. Shineha? How do you see technology entering into the realm of people’s inner world and mind? I would also like to hear your opinions on the impact on society as a whole and the impact on the formation of individual identity.

Dr. Shineha: “I believe that there are of course both merits and demerits to being able to know things that are unconscious or things that the person was not necessarily aware of or did not even know about. For example, the ability to proactively identify and intervene in stressful or painful situations that the person may not have been aware of has the benefit of making it easier to restore mental health and physical and emotional wellbeing by providing more appropriate care.

On the other hand, there are disadvantages, such as the violation of the “right to remain unaware,” in that such data is taken without one’s knowledge, and in a sense, one learns of situations that one did not want to know about. I believe that the important issue is how to balance these issues and utilize the data in a good way.

I believe that data governance will become an important perspective at that time, as seen in the Japanese discussion and current situation, as well as in international research and policy discussions. This is because we are actually dealing with sensitive data. For example, we need to consider whether parents are allowed to look at their children’s data. On the other hand, if negative data, such as a decline in brain function, is revealed, appropriate intervention will have to be made. What kind of authority and structure would be needed to make this possible, and even that has not been decided. In such a situation, even if there is a possibility to acquire and utilize brain data, it may be difficult to take concrete actions. We want to avoid such a situation, and because we want to prevent such a situation, we need to establish rules by carefully determining “what kind of data will be used, by whom, and how it will be used,” “whether such use is permitted,” and “whether it is acceptable.

It is necessary to operate in accordance with this. Our example is still a small step, but I hope that this kind of discussion and efforts to establish governance will continue to expand.

Ishido: “Because the data is sensitive, I felt that it is extremely important for society as a whole to promote rule-making in terms of who makes the decision to use or not use the data and who has ownership of the data. From this perspective, it is essential to foster literacy education on the use of information and data from an early age, and this is something I have been working on myself. As I listened to your talk, I strongly felt that similar literacy education and awareness-raising activities on brain information, which Dr. Shineha and his colleagues are working on, should eventually be extended to the educational field. How do you think literacy education and educational activities on brain information should be designed and implemented in society and educational settings in the future? We would be very grateful if you could give us your opinion on the future direction.

Dr. Shineha: “You are right, and I think it is important to create educational content that includes this kind of content, technical content related to the use of brain information, and scientific mechanisms, as well as more explanations of the impact of social impact, tolerance of thinking skills related to discussions, and the development of educational content. I think it is important to create educational content that includes the mechanisms of scientific internal facts, or more explanations of the impact of social impact, tolerance of the ability to think and develop the ability to debate.

However, as I said, if the content is created by researchers alone, it tends to be too difficult, and the content may be considered a bit different from the educational field. I believe it is necessary to work together with teachers and other people involved in the field. As a researcher and practitioner, I would like to actively engage in such work in the future. That is the first point.

Secondly, does it fit or not with the so-called science and science-related educational curriculum in current school education, or will it be a field of free research? Should we still do the activity of including it in science, or should we practice it as a ‘private school’ separately from it, we have not yet considered these issues.

We would like to consider how we can feasibly incorporate it into the actual educational curriculum, or if it is difficult to incorporate it into the curriculum, how we can develop educational content in a different way, or how we can make it more open.

Let me ask Mr. Ishido a question as well. For example, I believe that educational content on neurodiversity is being developed in various forms. What kind of education and content related to neurodiversity are you seeing that you are getting a good response to? Also, what specific activities, such as “Brain World for Everyone,” do you think should be undertaken now?

Ishido: “First of all, I feel that the term “neurodiversity” itself has not yet fully taken root or spread in Japan. In terms of diversity, even gender diversity has not been fully realized, and my perception is that we are not even at the starting line of discussions on brain and neural diversity.

What I would like to do now, therefore, is to create a place where people from diverse backgrounds can gather and discuss “how to envision a society based on the diversity of the brain and nervous system. Then, we will gather and share the knowledge of those who have the tools and means to realize this vision. Our first goal is to build a platform that will serve as the foundation for such efforts.

In Japan, this area is still in its infancy. On the other hand, there are many areas for improvement in the field of education, as evidenced by the concern expressed by the United Nations regarding separate education for inclusive education. Not all education in Japan is lagging behind, but there are still many things that can be addressed. The reason we have been promoting the “one device per person” environment is to establish an infrastructure that can provide reasonable accommodations for all children. We feel that there is still a lot of potential and a lot of work to be done to build this kind of infrastructure.

We would like to continue to move toward the realization of a neuro-diverse society, carefully building on our efforts one by one.

New technologies need to be paired with public welfare systems

welfare policies to be implemented in society.

Ishido: “I mentioned earlier that ‘dialogue and discussion are important,’ and at the last “Brain World for Everyone” we invited science fiction writers to join us in a dialogue and discussion about how we can shape the “next era of normalcy” that we are aiming for by utilizing neurotechnology and brain tech. The background of this event was to provide a forum for discussion. The reason for holding this event was the recognition that the most time-consuming part of social implementation of technology is its acceptance by society.

In the EdTech area, there has been a lot of resistance to bringing digital into the education field, and considering that it took 15 years to introduce one device per student, it is necessary to have discussions not only among technologists and policy makers, but also among diverse actors, including users, about “what kind of technology is this,” “what are the benefits and what are the risks,” “what should we do to avoid risks,” and “what should we prepare for? What should we do to avoid the risks?” These questions need to be discussed not only by engineers and policy makers, but also by various actors, including users. Then, once social implementation becomes technically feasible, we want to shorten the time required for social acceptance as much as possible. This is the intention behind the holding of “Brain World for Everyone” and the background behind the creation of a place for dialogue and discussion with a diverse range of visitors and participants, including science fiction writers.

Dr. Shineha also uses the word “dialogue.” In the ELSI field, has the attitude of co-creation through repeated dialogue already taken root as a matter of course? I would be happy to hear your thoughts on this point as well.

Dr. Shineha: “I am assuming that you are aware that it is important to dialogue with various people. Interesting things come up when we talk. When we talked about Neurotech with the general public, we found that there was a great sense of anticipation. This includes a vague sense of expectation that ‘great things can be done. On the other hand, there are also many people who have the same vague sense of uneasiness, and some are concerned about the possibility of having what they are thinking in their brains extracted or having their memories read. However, such simple expectations and concerns are important, and they are the driving force behind the technology. I believe that the key is how well we can capture such voices with resolution.

I have an interesting statement that is not related to neurotech. At a previous event on regenerative medicine dialogue, he said, “It looks good that regenerative medicine can make people live longer and healthier, but if people actually live longer and healthier, they will be able to work because they are healthy, and their pensions will be postponed. If that is the case, then we don’t need this kind of technology. I think this is a clear example of the fact that if you want to make the best use of this technology, it must be paired with public policy and social welfare systems to make the most of it.

In order to fully utilize neurotech and brain information, it will have to be combined with public welfare systems and welfare policies as well as science policies. Since I myself have not yet finalized my ideas, I think this is a homework assignment that needs to be considered.

Ishido: “Our goal is for “Everybody’s Brain World” to become just such a place for dialogue. When I appeared on a radio program the other day and introduced “Everybody’s Brain World” and “Chomoro,” the MC commented, “Being able to see brain information is like being stripped naked.

Hearing these words, I was reminded of the importance of creating a forum for discussion that leads to a deeper understanding based on accurate facts, so that many people can take it as their own personal matter.

From this perspective, I would like to ask you about the guidelines you have established for brain information. I would be very interested to know what kind of efforts Dr. Shineha and his colleagues are making to make these guidelines permeate society so that many people will think about them for themselves and deepen their discussions.

In the area of ELSI, we believe it is extremely important to involve not only experts but also the public and to think together through dialogue. If you have any ideas on how to achieve this, or if you have any examples in Japan or overseas of how this method has worked or how it has been effective, we would be very happy to hear about them.

Dr. Shineha: “As with our group, and with other countries and groups, I don’t think there are many best practices that will work. At this point, I feel that we are in a phase where we are trying to accumulate as many good things as possible.

It is interesting that you mentioned earlier that there are many horizontal letters. I can’t think of any other way to describe “data governance” in the guidelines, but again, many people don’t get the idea when it is written in horizontal characters. We are still lacking in such rudimentary efforts to somehow translate such terms into Japanese. I feel that we have yet to share information that includes such efforts.

What I also liked about the other groups was that they seriously took the time and effort to involve the public and stakeholders. For example, the researchers in the neurorights movement, which is a movement for the right to use neurotechnology, were seriously involved in discussions and dialogues with the public and other concerned people, and I sensed a lot of momentum because they were so seriously involved. I think the key to involving the general public is to increase the number of serious participants.

Ishido: “This year marks the third year of “Brain World for Everyone,” with 33 exhibitors in the first year, 55 in the second year, and 77 this year, expanding in size each year and attracting many people involved in this field from all over Japan. As I myself would like to further increase the intensity of individual discussions, I would be delighted if you would take advantage of this opportunity to actively participate in the discussions.

Neurotechnology is a technology that has the potential to bring about major changes in human understanding and the design of society itself. That is why many people have high hopes for its potential, but at the same time, they also feel scared. Careful design from an ELSI perspective is essential in implementing such technology in society. I would like to ask you, what do you think is the most important design concept from the viewpoint of ELSI when implementing neurotechnology in society? We would be very grateful if you could tell us in your own words.

Dr. Shineha: “From my own personal point of view, I believe that the introduction of new technologies and knowledge, as well as neurotech, will reduce the number of people who are unhappy even by one person. No one would want more people to be unhappy or become negative due to discrimination, even if they are trying to start something new and interesting. That is why I think the essence of this kind of activity is to prevent such things and reduce the number of people who would be negatively affected by such things, even if only one person.

Ishido: “I think you are right. At the same time, I feel that it is important not to let technology penetrate into all areas, or in other words, “areas where technology is not introduced. I think that it is also essential to avoid excessive use of the power of technology and to intentionally draw boundaries when considering social implementation. In that sense, I would like to ask you, Dr. Shineha, what do you think is important for technology not to do?

Dr. Shineha: “This may sound like a change of pace, but when technology comes out, it arouses absolute desire. How can we control that, but not overstimulate it? I think it is a struggle between the two. If that conflict is successfully resolved, I think the possibility of unhappiness as I mentioned earlier will decrease. It may be an overstatement to say that we need to control that part, but I hope that we can ensure such protection by creating a system and designing a system well so that greed does not run too far out of control.

Ishido: “I believe that many of the exhibitors are the target audience for the guidelines exhibited by Dr. Shineha. So, I would like to ask you how you would like the exhibitors to use these guidelines and how you would like them to make use of them. Also, I would like to ask you what kind of dialogue and co-creation you hope to generate as a result of this exhibition.

Dr. Shineha: “We do not believe that the guidelines we have created are the best ‘solution. That is why we hope that a variety of people will take a look at the guidelines and use the points that they think could be useful in a good way. Rather than using them all as they are, we would like nothing more than for you to use them only where you think they could be of real use.

Our guidelines themselves are still in version 1. They need to be improved. We would like to update them based on what we discussed at the actual “Brain World for Everyone” event, and then move on to version 2 and 3 to better suit the current situation.

Ishido: “As Dr. Shineha said, our goal is to increase the number of happy people through technology. On the other hand, we also need to be cautious so that technology is not used in a way that creates unhappiness, and we feel that it is important to face new technology with an appropriate sense of distance, neither expecting too much nor fearing too much. Thank you very much for your valuable talk today.