Do eyes lead to a better understanding of the mind than the mouth? From eye contact and body movements Finding the best way to support the child

12/3/25

The Neurodiversity Project, sponsored by B Lab, aims to realize a society in which the diversity of the brain and nervous system is respected and everyone is able to demonstrate their abilities in their own way. The featured speaker in this Neurodiversity Project interview series is Dr. Mikimasa Omori (Picture 1), Associate Professor at the School of Human Sciences, Waseda University. Mikimasa Omori’s laboratory has conducted a research project titled “Do the eyes lead to a better understanding of the mind than the mouth? and exhibited the results of their research at the “Everyone’s Brain World 2025 – Super Diversified” exhibition. Nanako Ishido (Picture 2), Director of B Lab, spoke with us about the specifics of the exhibit, the background of their research efforts, and future prospects.

> Interview video is also available!

Supporting the speech and behavior of children with developmental disabilities and

increase the child’s options for the future

Ishido: “Hello everyone. In the Neurodiversity Project interview series, we are joined today by Dr. Mikimasa Omori of the School of Human Sciences, Waseda University, who exhibited at “Brain World for Everyone” for the first time this year. Could you tell us about your exhibit and research at “Brain World for Everyone?”

Dr. Omori: “I mainly support the speech and behavior of children with developmental disabilities. This time, I exhibited at “Everybody’s Brain World” under the theme of “Do eyes speak louder than words when it comes to understanding the mind?” I exhibited under the theme, “Do eyes lead to the understanding of the mind as much as the mouth does? The reason behind my involvement in this kind of research is that I originally majored in psychology at Keio University’s graduate school. In addition to research, I have also been working as a certified psychologist in the field. (Picture 3)

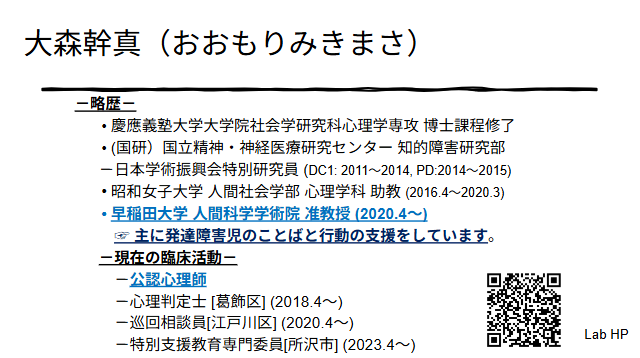

My laboratory is engaged in research on children with the mission of “increasing children’s options for the future. Behind this mission is the idea of “thinking while questioning common sense,” as in, “increase what you can do by questioning what is natural,” “increase what you can do by seeing what you cannot see,” and “increase what you can do by questioning the way you are taught. We are continuing our research by using psychological elements in the area of behavioral support, as well as neuroscientific approaches such as measuring eye movements and motor function measurements, and by combining these approaches with “what we can understand about children’s condition. (Picture 4)

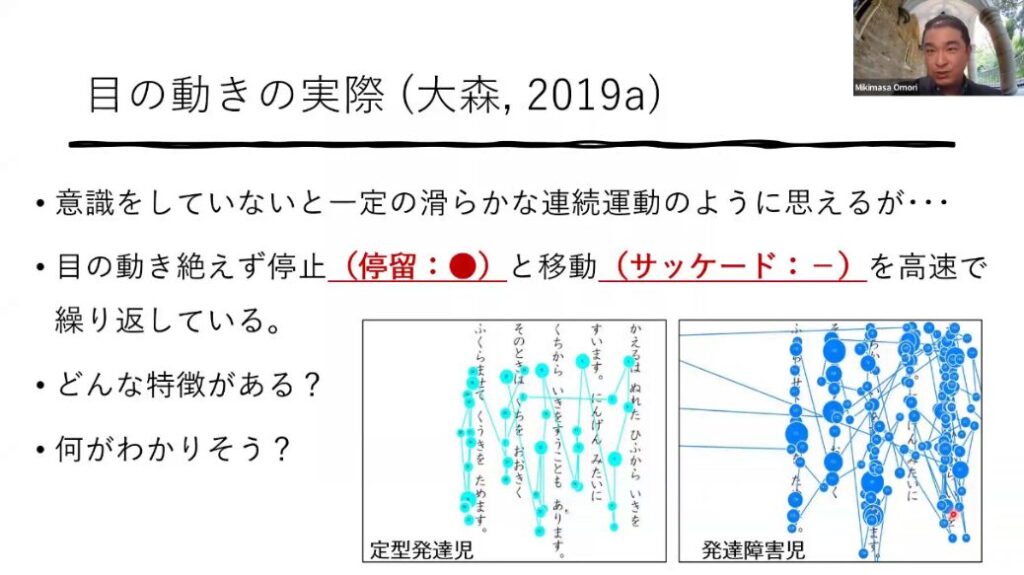

The theme of this year’s exhibition is whether eye movements can reveal the movement of the mind. When we actually measure eye movements with a device, we can see differences between children with regular development and those with developmental disabilities. (Picture 5)

Each blue or light blue “circle” indicates the movement of the eye. You can also see that there are differences in size. While the eyes of children with regular development move as if they were flying through clusters of meaning, children with severe disabilities who have difficulty reading are reading letter by letter. This means that even though they are reading, it does not lead to comprehension.

In the course of my research, I found that even though I could read well with ‘reading support,’ it did not lead to understanding. When I wondered what was going on, I happened to find a device at the university that could measure eye movements, and when I used it, it became clear to me that ‘if there is such a difference, it must be difficult to read. Based on these results, I rethought the methods of intervention and training for children with developmental disabilities, and began to support them, which is when I started my research on eye movements and mental states.

In this way, we have been assisting students in reading and writing hiragana and kanji, and recently we have been applying this assistance to English as well. For example, research has shown that teaching phonics, which shows the relationship between letters and sounds in English with only 9 words, can lead to the ability to read another 80 or so words.

Originally, we only provided this type of support, but when we conducted a study in an English class to see if school adjustment improves when students are able to learn, we found that for six children, problem behavior scores decreased when they were able to read and write in English. The results showed that the learning outcomes led to behavioral changes associated with the learning.

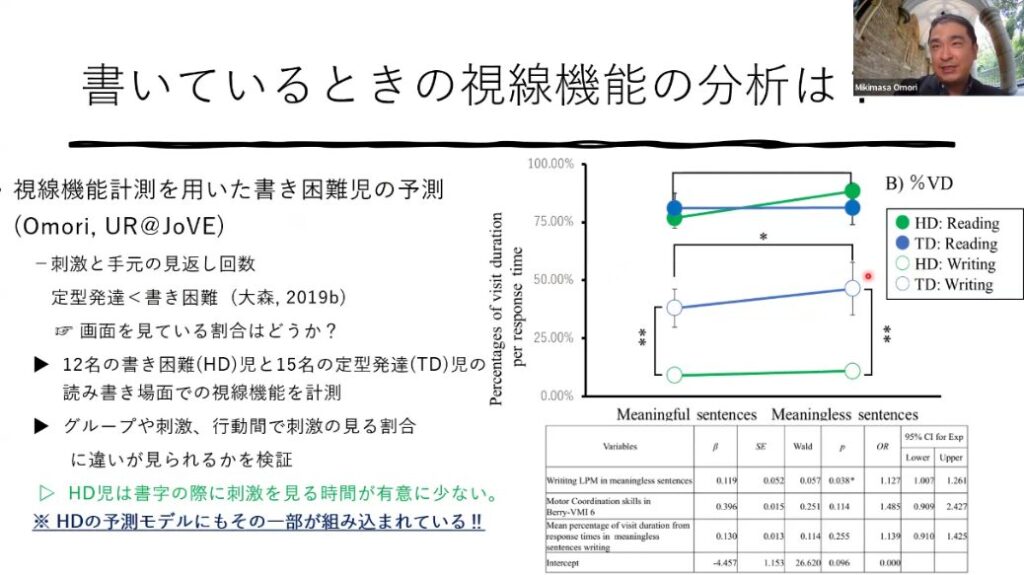

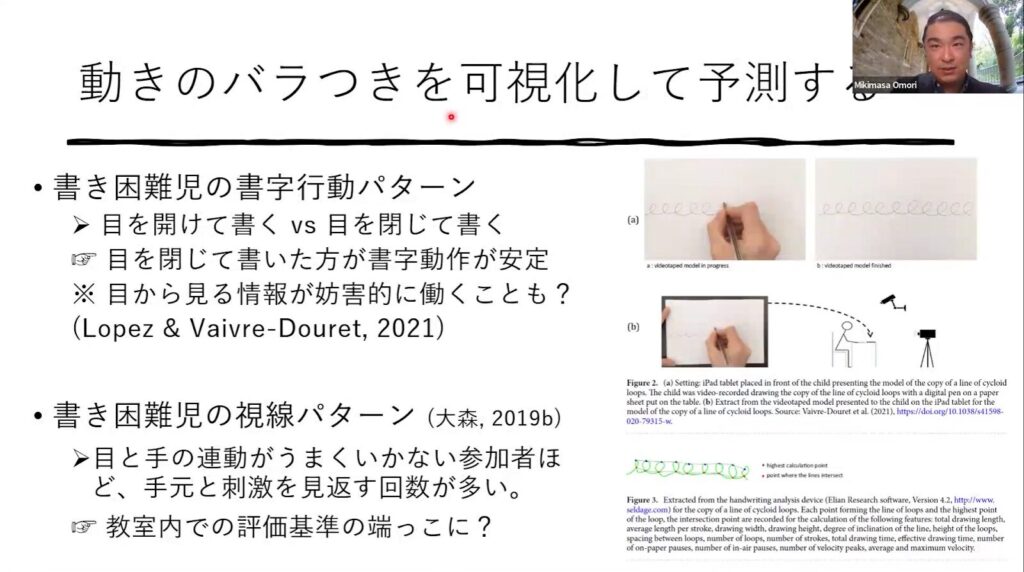

The study also uses eye function measurements to predict “children with writing difficulties. There have been many studies that have measured eye movements when reading, but not much research has been done on eye movements when writing, because the eye movements are off to look down. Therefore, in our laboratory, we are actually conducting research by measuring eye movements while writing. We measured both “reading” and “writing” because previous research had shown that children with writing difficulties would scurry up and down. We measured both reading and writing. We found that while there was no significant difference in reading, the difference between the blue and green circles was larger in writing. (Picture 6)

It was observed that children who were not good at writing would only look down instead of looking forward. Therefore, we are still researching the suggestion that practicing writing by looking forward will help them become better at it, and that it would be good to communicate this to schools along with the number of times they scurry.

From body movements as well as eye movements

Early prediction of ASD and hyperactivity

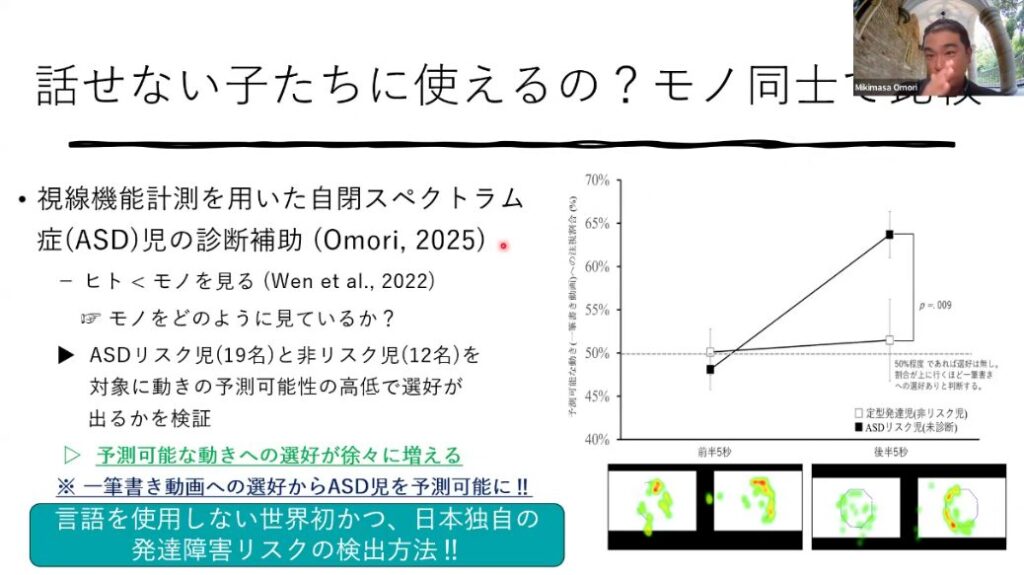

This kind of research based on eye movement has been conducted overseas for 10 to 20 years. In Japan, there was not much progress, so I started my research with the idea that it could be used to predict the diagnosis of children with autism and other communication difficulties. I had heard that one of the characteristics of autism is “obsession,” so I simply wondered if I could somehow incorporate that obsession into the eye movements. We measured which one the viewers were more interested in and watched for longer . (Picture 7)

We put out two videos at the same time and asked the children to watch them for a total of about 10 seconds. When we analyzed the first 5 seconds and the second 5 seconds, we found that in the first 5 seconds, the children looked at the right and left sides for about the same length of time, but in the second 5 seconds, as they approached completion, autistic children showed a characteristic of looking at predictable single stroke figures for a long time. We have found that this characteristic can be seen in children as young as 3 years old, and we are now promoting this method as the world’s first and unique Japanese method for detecting developmental disability risk that does not use language.

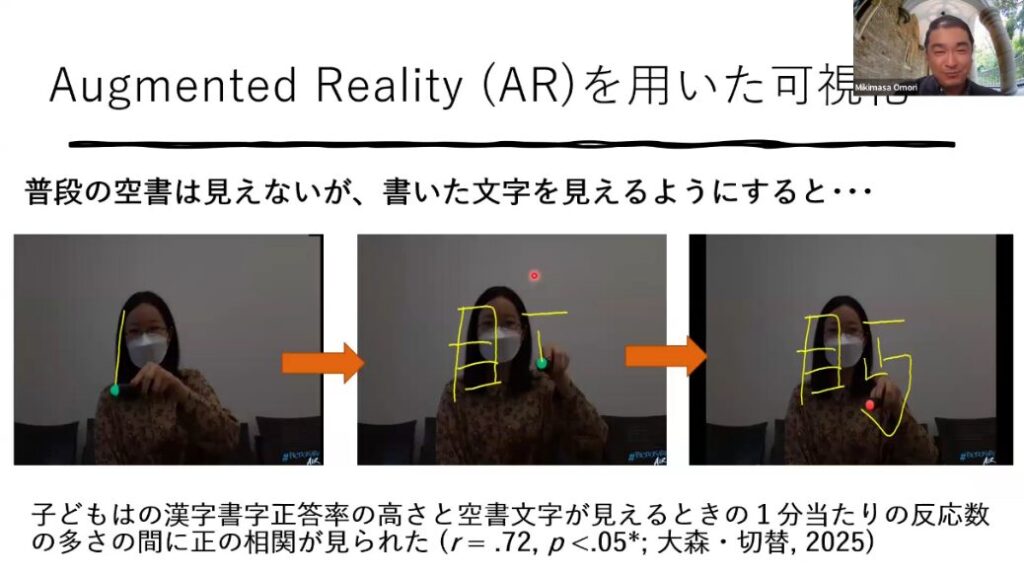

We also try to visualize many other things. In school, we may have done the “sky writing” exercise, in which we all wrote the Chinese characters for “mountain” and “sky” (1, 2, 3), but I wondered if we could really remember them, so I experimented with a pen that could write in augmented reality (AR). (Picture 8)

We are also utilizing a glass-type eye camera. We are planning to look at the characteristics while analyzing the data. (Picture 9)

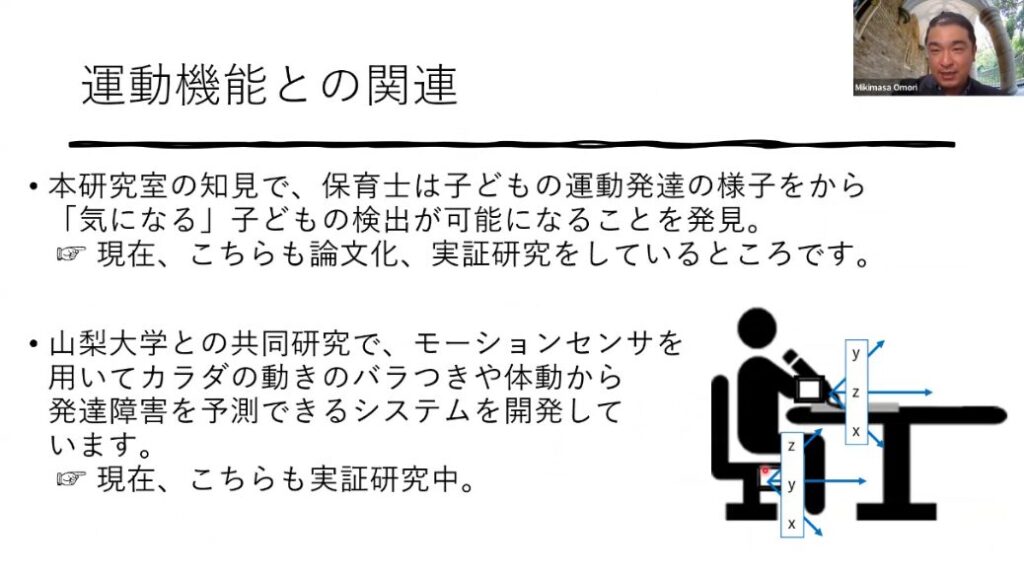

Until now, we have been trying to predict various disabilities and difficulties based on eye movements, but it is difficult to introduce this method to the field. We have learned from personal experience that it is especially difficult to introduce the system to schools, educational facilities, kindergartens, and nursery schools, so we decided to focus on body movements to see if we could simplify the system a little more. (Picture 10)

An example of what variation is often used is the swinging of a baseball or tennis ball. The reason why we do the swinging is to make the movements repetitive and reproducible. Perhaps the sports that we are not good at should have a lot of variation in movement, so that is where we came up with the idea for this research. The research used eye trackers and cameras, but we are also researching whether we can acquire data by utilizing sensors as well. (Picture 11)

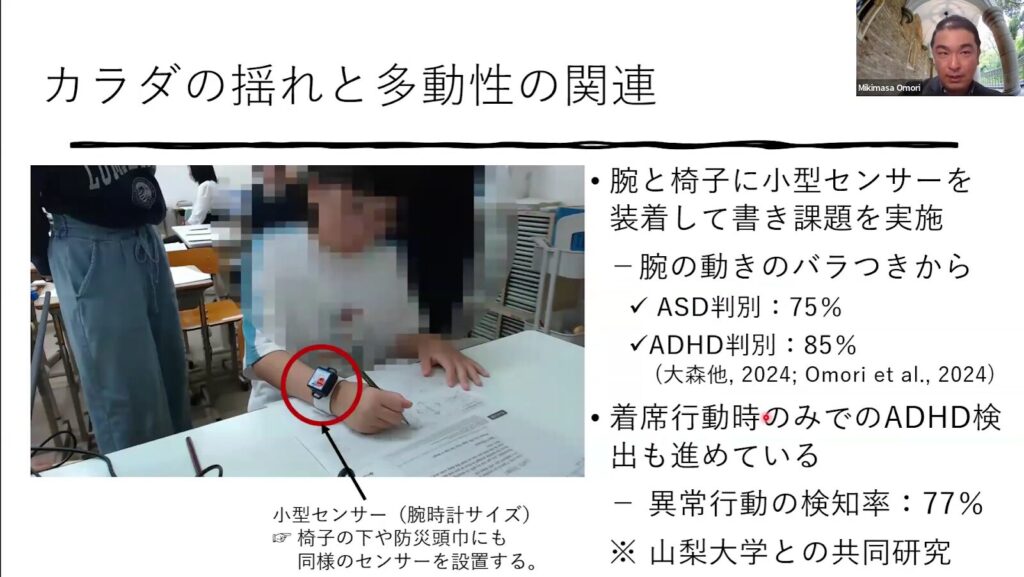

In fact, we are collaborating with a research group at the University of Yamanashi to see if there is anything that can be predicted from the variations in body movements that have occurred by attaching sensors to arms and chairs in this way.

As far as we currently know, data has come to show that ASD and hyperactivity can be detected up to 70-80% based on variations in arm movements while wearing such small sensors. We do not yet know if this is really possible, but I can tell you that the percentage of detectable cases is about this high using the data we have. (Picture 12)

Explore through “seeing,” “hearing,” and “speaking” to

consider what kind of support can be provided to the child.

This is a rough description of my research on the experiment so far. The research of exploring the mind through the eyes is not only focused on the aspect of supporting developmental disabilities, but also on various other aspects such as those related to anxiety, the relationship between facial attention and depression, and factors that contribute to communication difficulties in the presence of multiple human beings. We hope that the exhibition will deepen our understanding of the possibilities of such various aspects. (Picture 13)

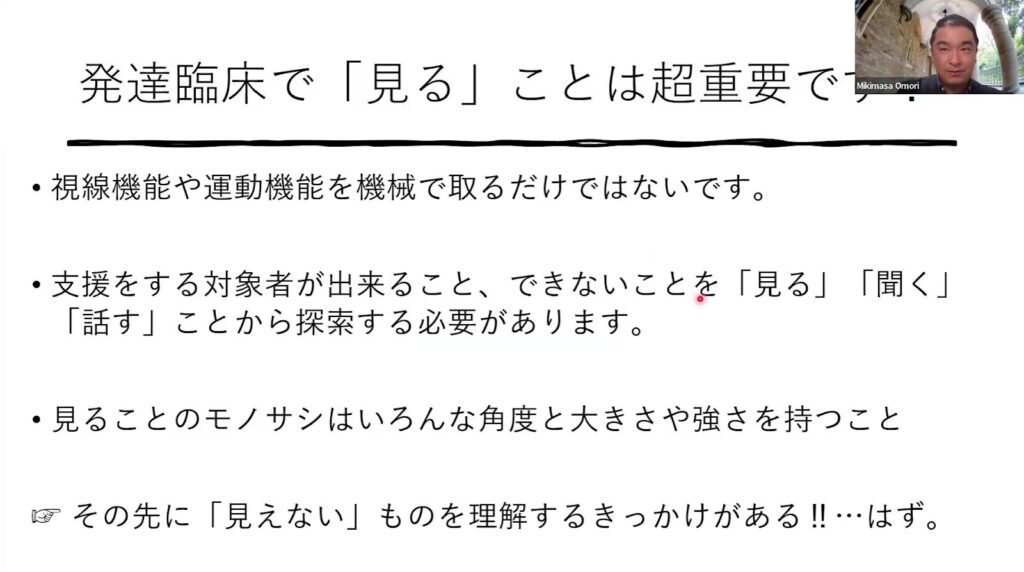

In my research area, developmental clinical psychology, “seeing” is very important. I believe that the basis of developmental clinical psychology is not only to use machines to measure eye movement and motor functions, but also to “see” what the subject can and cannot do, and especially to explore what the child can and cannot do through “seeing,” “hearing,” and “speaking. (Picture 14)

I often talk about this in the field, and I also tell them that what is important is not only psychological support, but also to offer “physical support from a place that is not known” to the person in question. I spoke today as a practical example of this.

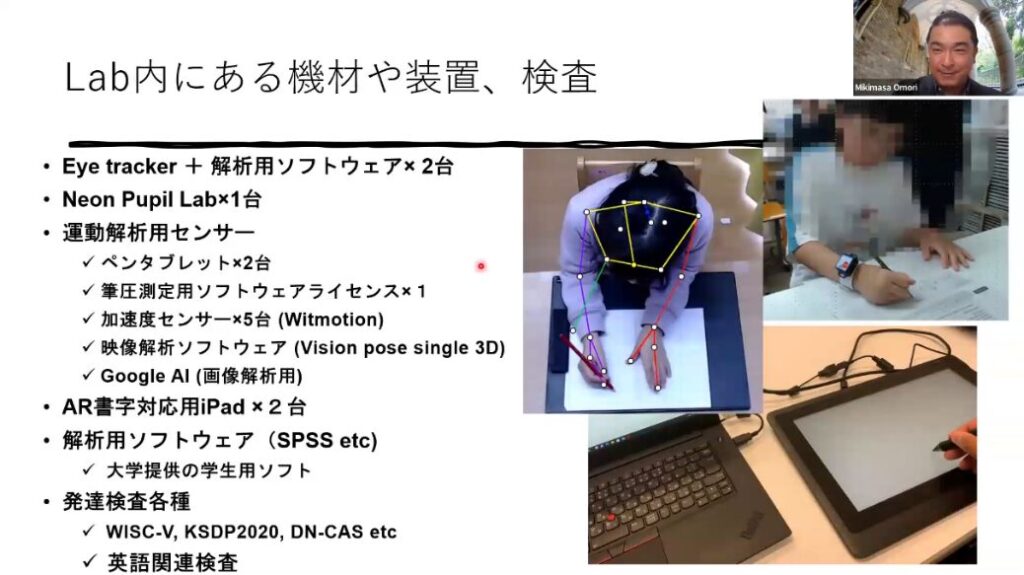

People say to me, ‘My university laboratory doesn’t look like clinical psychology because we have so many different kinds of equipment. I hope that in a way that is also an interesting aspect of psychological research. Thank you very much. (Picture 15)”

The earlier you find them, the

the more likely you are to play catch-up.

Ishido: “Thank you for your very clear explanation. I felt that your idea of increasing children’s future options and your perspectives of “questioning the norm” and “increasing what we can do” are highly compatible with the theme of our “Brain World for Everyone” project.

We believe that our neurodiversity project is an effort to create the “norm of the future. Our goal is to create a society in which each individual can expand his or her own options and realize a way of learning, working, and living that fits his or her own needs, while utilizing the power of technology. In this sense, I listened to the professor’s talk with deep empathy.

I would like to ask you a few questions about your research on early detection of ASD and other conditions through eye movement. While there is great significance and importance in early detection of characteristics through observation of viewpoints, I believe that ethical and social considerations are also essential. What do you think about its significance and ethical and social considerations?”

Dr. Omori: “As for the significance of early detection, research has reported that simply the earlier it is found, the more likely it is to play catch-up. And research has also shown that by providing appropriate intervention at an early stage, it is easier to make decisions that increase the child’s options to increase his or her tolerance.

In other countries, a diagnosis has the advantage of being able to receive support from public services and insurance coverage, so it is recommended to detect the disease at an early stage. However, in Japan, there is still a manpower problem and some people do not want to be diagnosed.

The diagnosis of autism is currently made at a median age of about 3 years old in Japan, and at an average age of about 7 years old. It is just before the child enters elementary school, and people are in a panic about what to do. However, in clinical practice, it is known that it becomes a little more difficult to catch up when the child is around 7 years old, so I think it would be good if this could be implemented together with, for example, legal checkups to detect it.

Also, doctors are very busy and I think it is very difficult for them, so I hope that we can create a decision-making process onsite to initiate support without waiting for the doctors’ diagnosis itself,” he said.”

Ishido: “On the other hand, I think that some psychiatrists point out the negative effects of immediately labeling a child as having a developmental disability if, for example, even the slightest problematic behavior is observed at school. I am aware that there is an argument that while a diagnosis provides support, developmental disabilities are shaped by the interaction of the individual’s characteristics and the environment, and that because of the spectrum, a blanket labeling may not always be appropriate. I am sure that Dr. Omori has thought about how to balance these issues and has struggled with it in his research and practice in the field. We would be very interested to hear about your experiences and thoughts in this area.”

Dr. Omori: “For me personally, when it comes to whether a diagnosis is necessary or unnecessary, I am in the position of thinking that it is not necessary with regard to developmental disabilities. It is the target of my research, and there are a variety of children who cannot sit in a chair, whether they are diagnosed or not. I have been doing this because I consider it my job to create the support that I can provide for these children.

However, there is a tendency to think that “it is easier to think in terms of diagnostic characteristics” rather than looking at behavior in detail. Of course, there are people who are conducting research based on this approach, and there are situations in which this is necessary. I approach my research and practice from a different perspective, so if there is something you would like to do with me in response to my research and efforts, let’s do it! I also talk to parents in the form of “If you want to work together with me on my research and initiatives, let’s do it!”

Ishido: “As you said, what is more important than whether or not a child receives a diagnosis is how we can reduce the child’s problems and make his/her daily life easier. The case you mentioned earlier, where the experience of learning English led to a decrease in problematic behavior, is a perfect example of this, and I thought it was a very nice story. I think that the positive experience of “being able to do more things” and “becoming good at studying” has a positive effect on behavior as well. If you have any other examples of how this ‘increase in what one can do’ or ‘growth in one’s strengths’ has led to positive changes in behavior, please let us know.”

Dr. Omori: “I used to specialize in learning support, so all I can talk about is learning management. But there are very few people in the field of psychology who can provide learning support. There are many people who specialize in psychological support, feeling support, and social support, but I always hope that the percentage of people who specialize in learning support will increase.

Overseas, the percentage of students who are maladjusted to school due to learning difficulties is quite high. In Japan, feelings and interpersonal relationships come first, and learning support is often neglected. However, when we talk with school teachers, some of them say, ‘We can do our best if we devise ways to support learning,’ so we are working together to provide such support.”

Ishido: “I was particularly interested in the fact that there are very few people in Japan who can provide learning support, and that research on detecting the risk of developmental disabilities from eye gaze has been ongoing for more than 10 years in other countries, but has hardly been addressed in Japan. What factors do you think are behind the difference between Japan and other countries?”

Dr. Omori: “You may be offended because this is a personal observation, but the laboratory where I grew up had a strong identity of supporting and researching something for children, so contact with children was a daily occurrence. However, when I started working in the psychological field, I think I was influenced by the fact that there are few people who specialize in working with children. In my own laboratory, I try to ensure that I have as many opportunities as possible to come into contact with children, so I hope to broaden my base there.”

Ishido: “Earlier, you mentioned a preference for single strokes and that children with ASD tend to prefer predictable stimuli. I feel that the clarification of these characteristics may provide many hints for the design of learning environments and methods of support. Based on your research so far, we would be very interested to hear about any new findings or discoveries that you have discovered, such as “this type of learning environment is good” or “this type of support can have a positive impact on learning.”

Dr. Omori: “In terms of image, I think it is similar to the English research I talked about. What I was working on as my theme was, simply put, ‘Does the way of learning change by manipulating the amount of showing? In Japanese homework, you tell students to read a lot of books and to read them over and over again. I think it would be difficult to tell children to read what I just mentioned about the movement of the eye, even if you told them to read. However, with research and practice, even these children will be able to understand words and short units.

I have tried to see if understanding can be improved by showing only the parts that need to be read and building up understanding, rather than showing the whole thing at once, like reading one part, then the next, then the next, and so on, gradually building up the parts that can be done, changing them over time.

It worked, and data shows that children with autism, learning disabilities, and typical development who were previously unable to read and comprehend a 300-word passage are now able to understand up to 80-90% of the text. However, the data also showed that these children were not successful with the method of ‘read the entire text repeatedly,’ so I believe that the method of presentation is an important part of the support in my research.”

Ishido: “Are you actually introducing such results to school sites and families?”

Dr. Omori: “Yes, we do. We provide it when schools call us and request to use it for independent activity time in support schools and support classes, and we disclose it upon request. People often ask me, ‘Why don’t you make an application?’ I answer, ‘I don’t know, because I don’t have the know-how. However, schools are more interested in something that can be done with ordinary PC software, so we try to disclose the production method and tell them how to do it.”

In order to realize a society of neurodiversity

Knowing people as people is most important

Ishido: “There have been many changes in how developmental disabilities are viewed. From the standpoint of your specialty, developmental clinical psychology, what changes has the concept of neurodiversity brought about in the conventional concept of developmental disabilities and the way support is provided?

Also, could you tell us whether new ideas and perspectives that differ from the conventional ones are emerging among developmental clinical psychologists?”

Dr. Omori: “Personally, I have been engaged in research with an awareness of neurodiversity in a sense, as I have picked up and supported problematic behaviors that are presumed to be associated with various disabilities as a cross-diagnostic target.

I personally have not seen such a big change, but when I give lectures and experiments to students, they sometimes say, ‘I thought they were children with a specific disability, but now I don’t recognize them because I have seen the characteristics of a different disability.

For me personally, it is a good thing to hear from students that they don’t understand, and I understand that they are thinking, ‘Why is what I am supposed to remember different? I try to talk to students in such a way that when they ask ‘why is it different,’ a theme of ‘let’s learn something new’ is created.”

Ishido: “The concept of neurodiversity that you envision, Dr. Omori, has not yet fully taken root in schools, and I understand that this is why you are struggling with it on a daily basis. Then, what do you think is the most effective way to change the way of thinking in order to spread this concept to schools, communities, and society as a whole?”

Dr. Omori: “I think that is also a difficult problem, but one thing I think is important, at the very least, is to ‘let people know about it. If they don’t know, they won’t be able to do anything. If you don’t know, many people will only try to keep you away. That is why I try to tell students and others that they should first try to get in touch with us.

I think we should actually touch it and then decide what we can do about it, because of course there are some experiences that are unpleasant and some that are favorable. So one challenge may be that too many people have never touched it.”

Ishido: “Neurodiversity is a movement that targets all people because all people have brain and neurological diversity. The central idea is not to regard the characteristics of each person as a disability, but to make the most of each person’s individuality, and to change society to such a society. On the other hand, it is also important to remember that in reality, there is a lot of suffering and difficulties in life that cannot be put away by “pretty words. Please tell us your thoughts on how you see a society that makes the most of the characteristics of the people in your society, taking this background into consideration.”

Dr. Omori: “I personally agree with a society that makes the most of characteristics. However, I think it is also true that one’s characteristics do not take precedence in every situation, so I sometimes think it is different to say that disability is the reason for excessive demands in drawing the line there.

Of course, this is true regardless of whether one has a disability or not, but I personally think it would be a good opportunity for both parties to communicate and share what they can and cannot do. It is a matter of talking and reconciling.”

Ishido: “When I actually observe your learning support activities, I strongly feel that you value each teacher’s ‘individuality. So, what exactly does it mean to value diversity? And how does this concept manifest itself in actual support and actions? We would very much like to hear your thoughts on this subject.”

Dr. Omori: “In fact, to what extent does diversity reflect in terms of behavior? I am sure that everyone is diverse, but it is important to be able to say what you want to say. We think about things like it might be more fun if children are able to assert themselves and not just say ‘yes’ and ‘no,’ but if they can say, say, 70% of what they want to say, for example. Providing learning support would be providing an option for them to learn that. So of course we tell them, ‘If they want it, we will provide it,’ and ‘If they don’t want it, we will refuse it.”

Ishido: “Are efforts to use technology to scientifically clarify and link the findings to support, as Dr. Omori is currently working on, spreading to the entire field of clinical psychology?”

Dr. Omori: “I am not sure. I used to work at a hospital research institute, so I think there is a lot of research being done on pathological conditions, but I probably haven’t done enough research myself. However, I believe that AI is being used to do something, so I think it is not impossible.”

Ishido: “Are the skills and literacy required of researchers who wish to enter the field of psychology also changing?”

Dr. Omori: “When it comes to providing psychological support, I tell them, ‘Communication skills are required, so they are important. Also, physical strength is important. If you are working one-on-one with a child, you will lose a lot of your physical strength. Also, as my co-researcher says, “The rice cake is the specialty,” so I don’t think it is necessary for a psychologist, for example, to complete information engineering and AI all on his/her own.

However, what I try to do and what I tell students is that, for example, if I have a request, I must at least make an effort to know the language and the content that the other side will understand. I say this to myself, and I also do it to students, so in that sense, I feel that my scope of defense has broadened.”

Ishido: “We are working to realize a neuro-diverse society, but what kind of neuro-diverse society do you yourself hope to see realized in the next 10 to 20 years?”

Dr. Omori: “I think the strongest wish is for people to get to know people. Nowadays, there are fewer and fewer opportunities to get to know people as people, regardless of whether they have disabilities or not. Looking at my interactions with my elementary school friends, in the past we used to be able to ‘let’s play’ outside, but now there are more things we have to do inside the house and less time to play outside, so how do we get to know people as people, including that part of their lives? I don’t think it is necessary to go back to the Showa period, but I hope that getting to know people in a different way will emerge. When that happens, some children can speak well in person, while others can speak well through texting, so I hope that this part of the process will bring out their individuality.”

Ishido: “What do you think each of us can do and what role should we play toward the ideal society you envision?”

Dr. Omori: “As a researcher, I think outreach is important, so I think we have to do that part. In the psychology industry, since certified psychologists have been qualified, I think awareness is spreading along with clinical psychology, but when we think about what to do next, it is important to know what to offer to what kind of target audience. Personally, I have been accompanying some of the one-and-a-half and three-year-old checkups, so I am wondering if we can make that part of our business more beneficial.”

Ishido: “You just mentioned the word ‘outreach,’ and there are aspects of ‘Brain World for Everyone’ that many people have participated in as part of our outreach activities. Finally, I would like to ask you about your expectations and prospects for “Brain World for Everyone” in the future.”

Dr. Omori: “Actually, I did not really like to appear in this kind of media. For that reason, there were parts of me that wondered what I should do, but I always felt that we needed to actively let people know about our efforts, so I thought this was a valuable opportunity for me to participate. Thank you so much.”

Ishido: “Thank you very much. We, together with Dr. Omori, will continue to further promote the “Brain World for Everyone” initiative to expand children’s future options.”