AI interactive robot that shares “nice experiences” among family members who live far away from each other AI Interactive Robot to Improve “Happiness

1/23/26

The Neurodiversity Project, organized by B Lab, aims to realize a society in which everyone can exercise their abilities in their own way, respecting the diversity of the brain and nervous system. In this Neurodiversity Project interview series, we will introduce the efforts of Professor Yutaka Hiroi (▲Picture 1▲) of the Department of Robotics Engineering, Faculty of Robotics and Design Engineering, Osaka Institute of Technology, who participated in “Brain World for Everyone” in 2025. The Life Support Robot System Laboratory led by Dr. Hiroi exhibited an “AI interactive robot that shares “nice experiences”” with family members who live far away from each other to let them know what is going on. Nanako Ishido (▲Picture 2▲), director of the B Lab, spoke with Mr. Hiroi about his research.

AI Interactive Robot Shares “Like” Experiences and Promotes Communication with Family Members Away from Home

AI interactive robot that encourages communication with distant family members

Ishido: “First of all, I would like to talk about the contents of the “Brain World for Everyone” exhibit.”

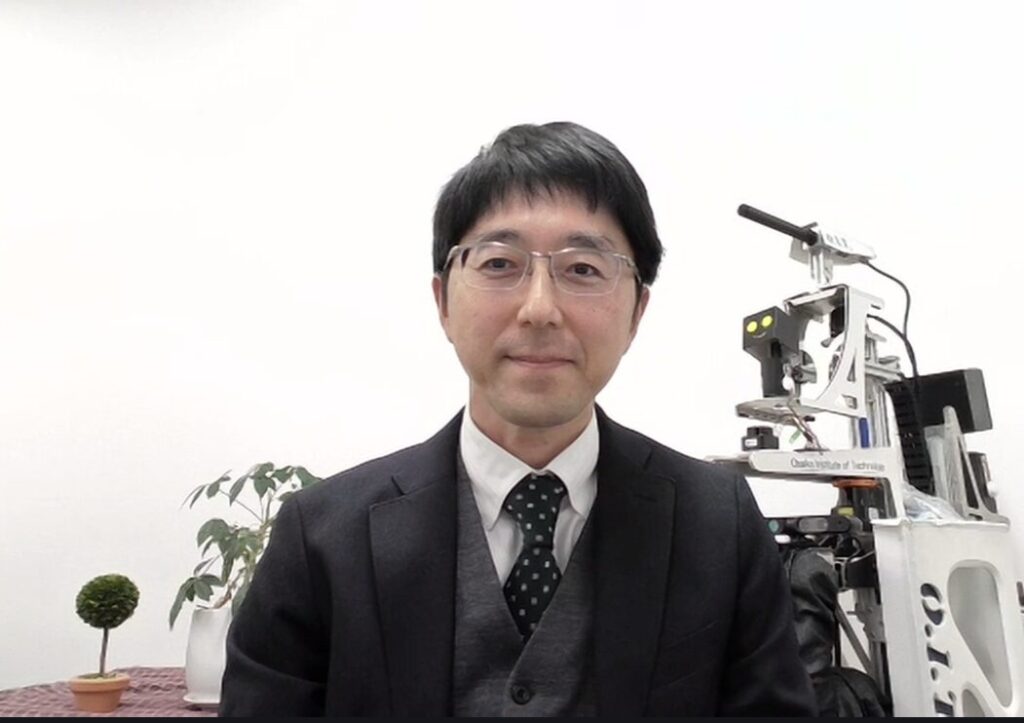

Dr. Hiroi: “At Minna no Brain World, we exhibited an AI interactive robot that shares “nice experiences. (▲Picture 3▲)

In this exhibition, we have prepared two scenes in which AI interactive robots will be used. The first was a scene in which parents learn how their children, who are college students living in a remote area, are living, and the second was a scene in which a grandmother learns how her grandchildren are living away from her. Visitors were asked to play the roles of the parents and the grandmother, and a demonstration was given in which they actually spoke to the robot to find out what was going on with the other person.

College students do not contact their families very often. It is a burden for parents to check social networking posts every day, and children may feel as if they are being watched. We thought it would be a good idea if both parties could talk to the robot, and the updates stored in the robot could be naturally passed on to the other party.

Of course, there is too much information if everything you tell the robot is conveyed to the other person, so the robot will summarize the conversation. In the scenario, what was good about the week, here expressed as a “nice experience,” is summarized and shared with you.

For example, by sharing only “nice experiences,” such as “I got a 100 on a test” or “I went on a trip and ate delicious food,” we hypothesized that this would improve each other’s sense of happiness. Families living far away from each other tend to drift apart, but we hope that the interaction with the robot will lead them to say, “Shall we meet up next time? Let’s actually use the robot for a demonstration.”

*Lesser: Dialogue with an AI dialogue robot

Dr. Hiroi: “Do you enjoy kites with your friends?”

Robot: “Yes, Kite-san is having a good time with his friends. (▲Picture 4▲)”

Dr. Hiroi: “Is there a mid-term test coming up?”

Robot: “Yes. Kite-san is just now approaching his midterm exam in mechanics of materials, and he is studying hard for the equation relating stress and strain.”

Dr. Hiroi: “What else are you learning?”

Robot: “Mr. Kite is also learning about the use of operational amplifiers and noise suppression, and he is studying grounding and capacitor placement.”

Dr. Hiroi: “I heard that Kite went to Asakusa, did he eat anything?”

Robot: “Yes. Kite-san visited Kaminarimon and Nakamise-dori in Asakusa, where he ate fried manju and green tea ice cream.”

*This is it.

If you ask the robot what he ate at Asakusa or what his midterm exam is coming up, it will give you an answer to that question. One of the key points is that you have to ask the robot about Mr. Kite to get an answer. Would you like to ask something, too, Mr. Ishido?”

*Lesser: Dialogue with an AI dialogue robot

Ishido: “What have you enjoyed most in the last year?”

Robot: “Yes, I think the most enjoyable part was being able to celebrate New Year’s with my whole family.”

Ishido: “Do you have any aspirations for this year?”

Robot: “Yes. I would like to take better care of my health and try to smile more.”

Ishido: “You said you enjoyed communicating with your family.”

Robot: “My family is my irreplaceable, emotional support, and most importantly, they are the ones who share my happiness.”

Ishido: “In contrast, how do you position robots?”

Robots: “Robots are reliable helpers in our lives, but they are no match for the warmth of a family.”

*This is as far as I’ve gotten.

Ishido: “Sore, Sensei.”

Dr. Hiroi: “That’s wonderful. The robot responded with an answer that I did not expect. It’s very positive. By the way, the robot just looked down, which indicates that it is thinking. I think this kind of motion is also important. If the robot does not move, the user cannot tell whether the robot is frozen or thinking. (▲Picture 5▲)”

Ishido: “Does this robot have a persona setting for a family living apart?”

Dr. Hiroi: “The scenario I talked about is the setting of college-age children living apart from each other.”

Ishido: “Are you making them learn that?”

Dr. Hiroi: “The robot is not trained at the beginning, but its persona was originally set up for the demonstration. The robot is not learning at the beginning, but rather, the persona was originally set up for the demonstration.”

Ishido: “I see. For example, in the second scenario, the grandmother thinks the robot is her grandchild and interacts with it. In that case, do you set up the grandchild’s information in advance?”

Dr. Hiroi: “The grandchildren also have a robot, so the information accumulated in the robot on the grandchildren’s side is sent to the grandmother. They do not speak to each other in real time.”

Ishido: “I assume that communication data is gradually accumulated through repeated dialogues, but how much basic information is set up in advance in the initial stage?

For example, if there is no minimum attribute information, such as “attends Fatty University” or “studies materials engineering,” it may be difficult to establish a natural dialogue with grandchildren, especially in the introductory phase.”

Dr. Hiroi: “I think it is better to set persona information, which are attributes, at the beginning. Otherwise, the AI may lie or talk about something completely different, and the conversation may break down.”

Ishido: “So you have a certain amount of attribute information in the initial stage, and the more you use the system, the more it learns about the content of the dialogue.”

Dr. Hiroi: “That is correct.”

From the sharing of “likeable experiences”

A desire to meet in real life is born.

Ishido: “I feel that Dr. Hiroi’s research presents a new and interesting way of relationship: communication through a robot. Compared to direct human-to-human interaction, does the fact that the other party is a robot make it easier to talk, or does it change the content or depth of what is said?”

Dr. Hiroi: “It is difficult to say that there is. For example, you call ChatGPT ‘Chappie’ and talk to it about your problems. There will be things that you don’t talk about or can’t talk about with a human partner that you can talk about with a robot. Companies are developing robots with this kind of demand in mind. I think the market will expand in the future.”

Ishido: “In a previous survey, more than half of the respondents answered that they would feel more comfortable discussing their problems with a generated AI than with their parents or friends. As the number of people who feel that AI is easier to talk to than their parents or friends is increasing, do you think that the addition of a physical being with a physical nature like a robot will further enhance this effect? If you have any research results or findings on this point, please let us know.”

Dr. Hiroi: “For example, this robot just made a ‘nodding’ motion, but there is a thesis that physical movements combined with dialogue can improve familiarity.”

Ishido: “I am also promoting activities in the EdTech area, and I feel that, at least for children, a robot with physical physicality is a lower psychological hurdle to starting a dialogue.

I am also interested in how the presence of such a physical presence changes communication among family members who live remotely. Is it correct to say that one of the goals of your research is to clarify such changes and their effects?”

Dr. Hiroi: “Rather than research, we are working from the standpoint that it would be good if we could support this kind of communication.”

Ishido: “I myself am very sympathetic to the objective you mentioned at the beginning of your speech, that by supporting communication among families living apart, the happiness of families is enhanced and families have a chance to actually meet each other.

Among them, I found the system in which what you say to the robot is summarized and shared with family members for a week at a time to be very unique and interesting. I would be very interested to hear about the design philosophy behind the idea of supporting remote family communication in this way in the first place.”

Dr. Hiroi: “At first, we were thinking of using only one robot, for example, to ‘help watch over the elderly’ by placing the robot only by the grandmother’s side. We had envisioned a scenario in which the grandmother would send a summary of what happened this week to her family, but we realized that this would not be a two-way communication. We realized that the grandmother might actually want to know how her grandchildren were doing, and that she might want to interact with them through dialogue with the robot.

We thought that if the robot could act as our grandchildren and tell us what they are doing in their daily lives, it would be a more enjoyable dialogue.

In order to achieve this, if robots with physicality cross each other, the dialogue will be more positive and last longer. It is important that this dialogue lasts. Dialogues often start out with mutual interest, but gradually become tedious and stop talking. So, to make the dialogue last longer, we thought of putting robots in both places and giving them the attributes of each user.”

Ishido: “On the other hand, I would like to ask from a slightly negative point of view. I believe that a robot learns through repeated interaction, and if it is a grandchild, for example, it will approach the behavior and speech style typical of grandchildren, but in reality, there may be areas where the robot does not learn sufficiently, and so-called halcyonation may occur. In reality, however, there may be areas where learning may not be sufficient, and so-called “halcination” may occur. In such cases, will there not be a sense of discomfort, such as “That’s not quite right,” or a gap between the image of the grandchild formed in the conversation with the robot and the actual image of the grandchild when you meet the grandchild in person? What are your thoughts on this point?”

Dr. Hiroi: “I think that is true. Conversely, I believe that the discomfort or gap between the two will lead to a chance to meet in person. For example, if the robot is learning in a strange way, and when you actually meet it, you feel that it is totally different, you may feel that you need to meet with it more often.

If you are satisfied with the interaction with the robot, you can solve the problem by simply talking to the robot. There is no longer a need to meet with the person in person. That’s not the point. The point is that we want the family to meet in person.”

Ishido: “Earlier, I mentioned that an increasing number of people are finding it easier to consult with generative AI, but as the number of cases in which people actually use generative AI as a consulting partner grows, there have unfortunately been reports of cases that have led to undesirable results.

That is why I feel that in your research, Dr. Hiroi, it is important not to simply complete the dialogue, but to create a mechanism that “makes people want to meet in real life” and “leads to actual relationships with real people. Please let us know how you are devising and designing in this regard.”

Dr. Hiroi: “That is the ‘good experience. It is based on the hypothesis that ‘if you hear about a good experience, you may actually want to meet the robot. In reality, they may be saying bad things about the robot, but if we can convey only ‘good experiences’ from their interaction with the robot, it will lead them to say, ‘Next time we meet, let’s go to a nice restaurant together.”

Ishido: “I also feel that a certain level of information editing and control is characteristic of the program, such as summarizing the dialogue content and delivering a weekly summary, and extracting and sharing positive information. What kind of changes have you seen in communication and relationships among family members as a result of the delivery of such edited information?

We would also like to hear about the results and trends you have achieved so far, as well as how you plan to develop the editing and delivery of information in the future, I would like to hear from you about the results and trends that are evident at this point, as well as how you intend to develop the editing and delivery of information.”

Dr. Hiroi: “Currently, since it is for demonstration purposes, we divide the dialogue into three levels: negative, positive, and neutral, and send only the positive topics of the three to the other party.

Also, if you make one dialogue too long, it is easy for the dialogue to break down, so we make adjustments to prevent that from happening. I don’t think this will change much when we implement it.”

Possibilities for Neurodivergent Support

Deformation design lowers psychological hurdles

Ishido: “We at “Brain World for Everyone” are working to expand neurodiversity in society, but many neurodivergent people have a strong sense of difficulty with interpersonal communication.

Of course, I feel that these problems are not limited to neurodivergent people, but are common to many people in terms of communication difficulties. Based on these assumptions, I would like to ask you two questions again from the perspective of what can be done.

First, how does Dr. Hiroi view the phenomenon of “feeling psychologically more comfortable talking to a robot than to a person”? Second, what kind of support can a robot like this one provide to people who have difficulties in interpersonal communication? We would be happy to hear your thoughts on each of these questions.”

Dr. Hiroi: “There are many factors, but I believe it depends on the shape of the robot. Although the robot I am using was designed by me, I actually went through a lot of consideration regarding its design. For example, which color combinations for the eyes and body are easier to see and ‘friendlier’? I experimented to determine what ratio of head size to body width would be most “friendly,” and based on the results, I settled on the current shape (▲Picture 6▲).

If this place were to become a human face, it would become the other person itself, which could create a sense of rejection. To avoid this, we intentionally make it this way. This is the answer to the first point.

Regarding the second, the research itself is quite advanced. I have not gone into it, but I think that this robot can also assist without changing the design to some extent. Rather, it is more important whether the person who uses it can think ‘it is still good. Even if the person seems happy, he or she may not be, so I think it’s a challenge to figure out how to capture that.”

Ishido: “Many neurodivergent people feel that they are suffering from information overload. From this perspective, I found it very suggestive to intentionally reduce the amount of information and convey it to others, such as by summarizing the information and deforming the robot’s facial expressions. How does reducing the amount of information affect people’s understanding, sense of security, and ease of cognition? From the perspective of human cognition, we would be very interested to hear your thoughts and any findings you have so far.”

Dr. Hiroi: “That is a difficult question because it is not my area of expertise. I don’t know about the issue of the amount of information and cognition.”

Ishido: “You have realized the effectiveness of daring to thin out information through demonstration and verification to date, which is why your robots are also designed in such a way.”

Dr. Hiroi: “Well, if there is a lot of information, it would be difficult for even an able-bodied person to remember it all, so we are considering a minimalist design to see how much we can reduce the information.

However, this would be a matter of research. How much facial expression can be reduced, how much conversation can be reduced, and whether or not communication can be established on that basis would be a matter of research.”

Ishido: “I know that many people have trouble communicating with others, but I find Dr. Hiroi’s research very appealing in that it does not change the communication itself, but rather redesigns the environment in which it takes place. What previous research has been done on this approach of transforming the way people interact with each other by changing the environment or medium? If you have any relevant research or theoretical background, we would be very interested in hearing about it.”

Dr. Hiroi: “It is not yet clear how changing the environment will help. As for prior research, I think it may be relevant to talk about structuring the environment and using multiple robots to include humans in the communication between robots. I think there is talk of creating a space by having the robots interact with each other, so that the humans are drawn into it.”

Robots that play with children are the

The Ultimate Life Support Robot

Ishido: “Recently, the theme of how humans and robots can coexist has been frequently discussed in the media. I myself actually live with robots, and I feel that the way robots are perceived differs greatly depending on the country and cultural background. Japan is very unique and interesting in that, due in part to the influence of manga and anime, robots are not positioned as useful tools as in the West, but rather as friends or as flat, equal relationships.

I would like to ask you two questions. First, what do you think of the “existence of robots in Japan”? Second, how do you think this unique Japanese view of robots influences your research? We would be very interested to hear your thoughts.”

Dr. Hiroi: “I don’t have a clear definition of what a robot is. We do not define a robot because we believe that if we define the robot itself, it will stop its growth.

For example, the moment you say, “A robot is anything that controls itself intelligently,” you end up arguing, “Are other things not robots? I believe that a robot is something that you say, “This is a robot,” without defining what a robot is.

So the interactive robot I mentioned earlier is also a robot. My definition of a robot is that this is just what I consider a robot, and others may say that it is not a robot.”

Ishido: “You dare not define a robot strictly, but create a variety of robots, don’t you? What kind of worldview are you aiming for? Please tell us what kind of relationships and the state of society you ultimately hope to create through robots.”

Dr. Hiroi: “First of all, I want the robot to have a physical body. I want them to have a body, not just an agent on a display. Also, my motivation for my research is ‘I want to help people in need through robot technology,’ and ‘I want to solve minor inconveniences that are around us by using robots to assist them. I think that is the key point. Of course, everyone’s problems are different, so I don’t want to force my ideas on people.”

Ishido: “Rather than focusing on the definition of what a robot is, your stance is that you want to present solutions to problems that people have in their daily lives through technology and techniques. In this exhibition, I think you presented one way to address the specific problem of “communication between parents and children who live apart. On the other hand, there are many people who have various problems in their daily lives, including those that are difficult to verbalize, not limited to communication.

I would like to ask you what kind of problems you are currently interested in, or what kind of problems you have been strongly conscious of? How have you dealt with them and tried to solve them, and what kind of solution approaches do you have in mind for the future?”

Dr. Hiroi: “The style of my laboratory is ‘create what does not exist, make what does not exist. The style of my laboratory is to create what has never existed before, and to foster human resources who can create what does not exist (▲Picture 7▲).

For example, for the nine years from 2011 to 2020, before the Corona disaster, it participated in the “RoboCup,” a competition of autonomous mobile robots that think for themselves. Among them, I participated in the “RoboCup@Home League,” in which robots compete to see how well they can carry out tasks useful for living with humans in everyday home environments such as living rooms and kitchens, and I won the national competition three times (six times as runner-up). Since this is a competition for life support technology, various tasks were included, such as ‘bringing requested medicine by voice recognition’ or ‘acting like a waiter in a restaurant.

We needed to build a technology that could track human movement in the task to be solved, and when the World Congress was held in Nagoya in 2017, we received the “Best in Navigation” award for this technology, which is given to the best technology for navigation (▲Picture 8▲).

We have a core technology for detecting people, which enables the robot to follow the target person in a crowded place without making a mistake. We have not included this technology in the AI interactive robot we exhibited this time, but it can, for example, turn its face in the direction of a person without using a camera. We don’t have to worry about the possibility of personal identification if we use a camera.

Through participating in these competitions, I thought that “a robot that can play with children is the ultimate life support robot” (▲Picture 9▲).

Since children are unpredictable, they often behave in unpredictable ways, such as suddenly hitting or running. We began our research with the idea that the ultimate life support robot would be one that could perform its tasks while behaving safely and not breaking itself when struck by a child.

For example, we are developing a “robot that plays Daruma-san ga tumbled” using the technology for detecting people I mentioned earlier. Simply put, all we need to do is measure how far it has moved between certain times. The other is a “tag-playing robot. Basically, it follows the player and touches the player at the end. We are researching how to make this happen safely. For example, we are working on a robot that can be easily operated by a child who cannot go outside to play tag with friends.

It is operated with something like a gamepad, but if a person performs all the operations from a distance, the distance is not well perceived and the operation does not work well. On the other hand, if the operation is completely automatic, the player does not feel like he or she is operating the game. It would work as a “game of tag,” but it would lack interest.

So we created a system where the robot can be operated to some extent and automatically follow along in the middle of the game. We are announcing that this gives the feeling that we are playing together.”

Ishido: “Is this like a child in a hospital operating a robot from a hospital room?”

Dr. Hiroi: “This research is not limited to hospitals, but is intended to fulfill the wishes of people who, for various reasons, find it difficult to play with friends outside, but still want to play together.”

Ishido: “In our neurodiversity project, we also place great importance on increasing options. Those who have difficulty going outside can learn through the metaverse, for example, or work via robots. We believe that such an increase in options will itself enrich society.

In fact, I feel that lifestyles such as going to school or working remotely are already becoming a reality, as seen in the case of OriHime by Orii Research Institute Inc. I would like to ask you, in your own research, are there any themes or initiatives that you would like to further commit to in the future in order for people with limited mobility or face-to-face contact to participate more naturally and proactively in society through this kind of technology?”

Dr. Hiroi: “It is important to have continuity. To achieve this, I think it is important to make the research not ‘research for research’s sake only, but research that can be properly put to practical use.”

Ishido: “Practical application. I myself feel that it is very important how to implement the results of research into society. One of the goals of “Brain World for Everyone” is to create an environment in which excellent research by researchers can reach people in need as quickly and appropriately as possible.

I would like to ask you about the “continuity and seamless connection” you mentioned earlier. What do you think are the biggest hurdles to achieving this goal at this point? What do you feel are the biggest hurdles to achieving this goal, in terms of technology, systems, or social acceptance?”

Dr. Hiroi: “In Japan, it is the law. It is difficult to freely operate robots outside. Recently, things have changed a lot, such as the establishment of special zones, but I think this is one of the challenges.

Also, in Japan, there is a tendency to say, ‘You can’t move something unless it’s perfect. In other countries, I think there is a slight cultural difference, such as the tendency to try things out first.”

Ishido: “In addition to “Brain World for Everyone,” I am also running an event called “Slightly Further Interesting Future (Chomoro),” in which I am implementing the “Friend Robot” project, which focuses on the theme of symbiosis between robots and humans.

For example, despite the institutional restriction that robots cannot run on public roads, we have been trying to gradually advance social implementation where we can: a Halloween parade by robots in 2024, and an opening parade in 2025 in which humans and robots will participate together. By accumulating these small practices, we hope to gradually update regulations and social assumptions.

On the other hand, I feel that the psychological hurdle you mentioned earlier, that “in Japan, if it is not perfect, it is difficult to introduce,” is a very big issue. I myself have been involved in EdTech for many years, and have been involved in the development of a one-to-one terminal environment and the realization of mandatory programming education, but there was strong resistance simply because “digital” was involved.

How to improve social acceptability is an important theme for us and one of the roles we want “Everybody’s Brain World” to play.

In fact, I often hear researchers say, for example, “We want to be cautious about exhibiting technologies that use brain waves because we have not yet obtained sufficient evidence. On the other hand, I believe that “even if the evidence has not been fully obtained, making the public aware of the existence of such technology from the research stage will itself increase social acceptance and ultimately lead to faster acceptance. What do you think are effective approaches that researchers, practitioners, and society can take to reduce psychological resistance to these new technologies and increase their social acceptance? We would love to hear your thoughts.”

Dr. Hiroi: “As shown in the video featuring science education YouTuber Dengan, we actually used the guidance robot at the open campus.

I think this has been difficult to do until now. The reason we couldn’t do it is because people would say things like, ‘Is it safe to let people use such a thing?’ After thinking about what we could do to prevent things from getting too dense at the Corona Disaster Open Campus, we came up with the idea that it would be good if a robot guided us around. We actually used this robot at the tour. So this kind of robot was acceptable because of the Corona Disaster situation. For the students, they were able to get their first hands-on experience with the robot, so I think we both gained a lot from it.

The robot leads the way by keeping time with the person being guided. The person being guided then holds the robot’s hand. The robot has a special structure and control that allows its arms to extend. Because the arms extend, the person being guided can walk at his or her own pace, and can follow along even if he or she is blind. We have begun to use the robot as a campus guide as a “physical guiding robot” (▲Picture 10▲).

We believe that these small attempts will gradually spread throughout the world.”

Ishido: “We, too, are promoting neurodiversity activities, believing that the accumulation of small efforts will eventually lead to a large movement.

From the perspective of neurodiversity, what do you think are the areas and positions of people who should participate more widely in the future? We would also like to hear about the new future of communication that you envision, and how technology can provide support to those who have difficulties in their daily lives due to cognitive diversity.”

Dr. Hiroi: “I am a researcher of robots, so I would like to aim for robots to be involved in that, but some people may argue that it would be better if robots did not exist, so I think it depends on each person.

In the past, only robotics researchers were involved in the robotics field, but now we have participants from various fields, including sociologists. I think the situation has changed considerably from the past. I feel it is important to accept various opinions and ideas in the development of robots.”

Ishido: “Many researchers are currently participating in this project, and we would like to increase the speed of social implementation while thinking together about what kind of future image we can envision when such research is brought together. We hope that Dr. Hiroi will continue to participate in the next year’s exhibition and beyond.

In fact, I asked Dr. Hiroi in advance to make some requests regarding his exhibit this time, and as a result, I heard that he has greatly upgraded it to a form that can be used not only for seniors, but also for communication with young people.

Many researchers consider “Brain World for Everyone” as a milestone and say, “I will finish it by the day of the event because I have to finish it eventually. I am very much looking forward to the next exhibition. I am very much looking forward to the next exhibition. Thank you very much for your time today.”